published 27/08/2013 at 05:35 BST

published 27/08/2013 at 05:35 BST

who has died aged 91, was a French résistant during the war before being arrested and deported to Buchenwald; having survived the camp he joined the Foreign Legion, fighting for 15 years in

Indo-China, Suez and Algeria before taking part in an attempted coup to overthrow Charles de Gaulle.

His participation in the 1961 plot, hatched by four French generals to prevent de Gaulle ending colonial rule in Algeria, led

to disgrace and a 10-year jail sentence, of which Saint Marc served five. Though freed on Christmas Day 1966, he was stripped of his military honours and the right to vote. Gradually his

reputation recovered until finally, in 2011, he was appointed Grand-Croix de la Légion d’honneur – rehabilitation that marked the final twist in a remarkable life.

His participation in the 1961 plot, hatched by four French generals to prevent de Gaulle ending colonial rule in Algeria, led

to disgrace and a 10-year jail sentence, of which Saint Marc served five. Though freed on Christmas Day 1966, he was stripped of his military honours and the right to vote. Gradually his

reputation recovered until finally, in 2011, he was appointed Grand-Croix de la Légion d’honneur – rehabilitation that marked the final twist in a remarkable life.

Hélie Denoix de Saint Marc was born in Bordeaux on February 11 1922, the last of seven children in a well-to-do family. His mother, Madeleine (née Buhan), was descended from wine merchants; his

father, Joseph, was a lawyer of renown who had fought at Verdun.

Hélie was an unremarkable student at the Tivoli Jesuit college, taking an interest only in history, and dreaming from adolescence of a military career. Outside the classroom he spent happy

summers at the family’s farm in the Périgord, which he explored by bicycle.

With the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939, Hélie ’s elder brothers were called up, but he was still in Bordeaux by the time the Germans occupied France the following year. “It was a moment of

hopelessness, hate and rage,” he recalled later.

His beginnings in the Resistance were motivated simply by a desire to get to the family farm in Périgord once term had finished in Bordeaux; his parents had passes to cross to the unoccupied

zone, but Hélie had to sneak across into Vichy France.

In spring 1941 the superior of Tivoli college, Father Bernard de Gorostarzu, introduced Saint Marc to Claude Arnould, known as Colonel Arnould, head of the Jade-Amicol Resistance network . Saint

Marc was asked to take a package over the demarcation line, then made frequent trips between the Vichy and Occupied zones. Occasionally he would accompany Arnould, also known as Colonel Ollivier

, to the border with Spain or the Atlantic coast.

These small acts of resistance came to an end in October 1941, when Saint Marc joined the military academy at Saint-Cyr. The following June he failed his exams miserably and determined to flee to

Spain and, from there, join Free French forces. On July 13 1943 he was with 15 others being smuggled out of Perpignan towards the border when the lorry in which they were travelling was brought

to a halt by a German patrol and its clandestine passengers were arrested.

Suspected only of trying to flee forced labour in Germany, Saint Marc was spared brutal interrogation and taken to a holding camp at Compiègne; from there he was deported to Buchenwald, where he

became prisoner M 20543 and was forced into slave labour. In December 1943 he was struck down with pneumonia and dysentery, and seemed certain to die until a fellow prisoner nursing him, Hubert

Colle, exchanged his own hoarded reserves of food for 30 Protonsil pills . Eight days later the fever broke and Saint Marc began to recover.

In September 1944 he was moved to Langenstein-Zwieberge camp in the Harz mountains of central Germany, to dig out a vast network of tunnels where the Nazis wanted to build factories for wonder

weapons they hoped would turn the course of the war. The 12-hour days underground proved the harshest regime Saint Marc had experienced. “I adopted an animal existence: eat, sleep, survive,

that’s all,” he recalled.

Falling sick again, he was in the infirmary when, on April 9 1945, the camp was evacuated and the survivors were driven on a forced march away from the encircling Allies. Left behind, he was soon

in a hospital in Magdeburg. Aged 23, he weighed six stone.

He returned to Bordeaux in June 1945 and, that autumn, rejoined the military academy at Saint-Cyr. Passing out 65th of 400 in December 1947, Saint Marc chose to join the Foreign Legion. Within

nine months he was en route to Indo-China, where France was two years into a colonial war that would end with defeat in 1954.

Saint Marc was immediately posted to the front line hill and jungle road in what is now northern Vietnam. Known as RC4, the route was used by the French army to supply a chain of camps; it was

between these and the border of Nationalist China that it hoped to crush the Viet Minh. Shortly after arriving, Saint Marc was ordered to form a partisan unit at Ta Lung, on the river Song Bang

Giang, 600 metres from the Chinese border.

For a year, Lt Saint Marc was given total liberty within his zone of operations, leading his company of 15 partisans, 10 legionnaires, and two junior officers through local villages: arming them,

trying to form alliances, learning a little of the native Tho language, and leading raids into Viet Minh-held territory. In October 1949, however, Saint Marc watched as Mao’s forces overran the

Nationalist Chinese troops less than a kilometre away; suddenly the Viet Minh were able to fall back into a limitless hinterland across the border. For the French it was a stunning strategic

reverse, and two months later Saint Marc received the order to withdraw.

Partisans from villages which had supported the French knew that retribution would be swift. Saint Marc later described his lingering shame as his men prised locals’ fingers off the side of the

trucks carrying the legionnaires away. “Men, women and children clung on, and once forced off, sat crying in the dust of the roadside,” he said. “No one there would ever forget it.”

He returned to Indo-China in July 1951 and, as commander of a company of the 2 BEP (Foreign Legion Parachute Battalion) formed from Vietnamese volunteers, was promoted captain in October.

Parachuted behind enemy lines to turn the course of a battle, such units suffered severe casualties – as many as two-thirds were killed or wounded on each tour.

In late 1951 the French commander, General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny (whose own son, Bernard, had been killed in the fighting), attempted to draw the Viet Minh into a confrontation at Hoa Binh,

50 miles north of Hanoi. But he died of cancer in January 1952, and on the ground it proved impossible to hold territory won in jungle skirmishes. Saint Marc was soon ordered to evacuate once

again, in what he described as the hardest hand-to-hand fighting of his career.

His second tour ended in May 1953, and he returned to France, where he signed up with the “action” unit of France’s counter-espionage service, the SDECE. As French forces made a last stand at

their camp at Dien Bien Phu, he volunteered to return to Indo-China, only to arrive too late, the camp having already been overrun. Within months the Geneva Conference brought France’s role in

the fighting to an end.

Saint Marc was shipped straight to Algeria, where the anti-colonial Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) was launching its first attacks against French settlers. Stationed at Tébessa, on the

border with Tunisia, he took command of 3 Company of the 1 BEP (soon upgraded to REP, regimental status), leading ambushes and raids on nascent FLN forces in the Nementcha mountains, whose

southern slopes end in the sands of the Sahara.

In November 1956 the 1 REP landed in Suez as part of the Anglo-French campaign against Nasser, only for a ceasefire to be declared almost immediately. Saint Marc’s enraged men, longing for a

fight, soothed themselves by fashioning fishing rods and trying their luck in the Canal.

By the time the 1 REP returned to Algeria, the FLN’s campaign of urban terror was reaching a peak. Saint Marc and his men were transferred to Algiers in January 1957, a month marked by 112 FLN

attacks in the city. At the beginning of the following month he was selected to join the staff of Jacques Massu, the general who had been given carte blanche by the French government to restore

order in the city.

Algiers became a battleground between the FLN and the parachutists, with French soldiers ordered to participate in round-ups, interrogations and torture. Saint Marc was Massu’s liaison with the

press. As questions mounted about the brutality of his methods, Massu pursued the operation remorselessly, pressing through the Casbah until French forces had regained total control. Saint Marc’s

strategy with journalists was simple: “Don’t reveal everything, but don’t lie.”

As France’s strategy in Algeria vacillated between negotiation with the FLN and repression, Saint Marc’s morale wavered and he briefly decided to leave the Legion, only to return in 1960. Once

back he found that discipline was worsening as a French withdrawal began to appear increasingly inevitable. When three officers of the 1 REP refused orders, Saint Marc was promoted to

second-in-command of the regiment; he restored discipline and assumed full regimental control in April 1961.

Within days he was approached by General Maurice Challe, a veteran of the Second World War and counter-insurgency strategist in Algeria, and asked if he would consider joining a coup against de

Gaulle, aimed at preventing a French withdrawal from Algeria.

After less than an hour’s deliberation, Saint Marc agreed to lead the 1 REP in the coup, planned for the following day . Comically, the Saint Marcs had a dinner party invitation that night from

Bernard Saint-Hillier, another general, who was not in on the plot. The couple attended so as not to suggest that anything was wrong. Smiling through the course of dinner, as his men prepared to

overthrow the French state, was, Saint Marc later said, “one of my most disagreeable memories”.

After returning to barracks, he was telephoned by Fernand Gambiez, commander-in-chief of the French army in Algeria, also uninvolved in the plot. Rumours of a coup had reached Paris. “Everything

is normal here, mon général,” lied Saint Marc. “Not a vehicle is moving.” Ten minutes later the 1 REP was advancing on Algiers. Two hours later, at 4am on Saturday April 22, it was in place at

every major crossroads in the city, and was in control of government buildings and local television and radio stations.

The second phase of the coup was to parachute into airfields around Paris and seize control of the capital. Challe spent the weekend on the telephone, calling fellow officers and demanding their

support. Meanwhile, on Sunday April 23, de Gaulle appeared on television in his old military uniform, appealing to French citizens to rally to his support against “an odious and stupid

adventure”.

Soon it became clear that support for the coup was withering. In Algiers, Saint Marc and his men experienced a bizarre hiatus while the balance of power was being decided. He later recalled a

young Algerian approaching him and calmly discussing the various scenarios that might play out. “It was very relaxed,” Saint Marc noted, “despite the fact that we were there in Jeeps, with

machine guns at our sides.”

By Monday night it was all over. The 1 REP returned to barracks. Three of the four rebel generals made a run for it. Challe and Saint Marc were left to await the consequences of their actions.

“You are young Saint Marc,” noted Challe. “We are going to pay a heavy price. I will certainly be shot. Let me surrender alone.”

The following morning the barracks was surrounded and Challe and Saint Marc surrendered. The 1 REP was disbanded, and Saint Marc was flown to La Santé prison in Paris.

His trial began on June 5. He appeared in full uniform, and read a four-page statement: “One day not long ago we were told to prepare to abandon Algeria... and I thought of [Indo-China]. I

thought of villagers clinging to our lorries... of the disbelief and outrage of our Vietnamese allies when we left Tonkin. Then I thought of all the solemn promises we made in Africa, of all the

people who chose the French cause because of us... of the messages scrawled in so many villages: 'The Army will protect us. The Army will stay’.”

Ignoring the demands of the government, which sent written orders insisting on a 20-year jail term, the prosecutor, Jean Reliquet, pressed only for a term of five to eight years. In fact, a panel

of eight judges sentenced Saint Marc to 10 years in jail. (Challe received 15.)

After his pardon came through he joined a manufacturing firm in Lyon, becoming personnel director. After 10 years he found himself welcome again in the barracks of the Legion. In the late 1980s

he began to collaborate with the journalist Laurent Beccaria, who wrote his biography. Saint Marc then began to speak at conferences around the world.

He wrote or contributed to several books about war, including Les Soldats Oubliés (1993); Memoires (1995); Les Sentinelles du Soir (1999); and Notre Histoire (2002), written with August von

Kageneck, a German officer of a similar age, in which the two men discuss their differing experiences of the Second World War.

Hélie de Saint Marc, who in retirement lived in the Drôme, married, in 1957, Manette de Châteaubodeau, with whom he had four daughters.

Hélie de Saint Marc, born February 11 1922, died August 26 2013

Hélie de Saint Marc obituary

Saint Marc Hélie de

Hélie Denoix de Saint Marc ou Hélie de Saint Marc, né le 11 février 1922 à Bordeaux et mort le 26 août 2013 à La Garde-Adhémar

(Drôme)3, est un ancien résistant et un ancien officier d'active de l'armée française, ayant servi à la Légion étrangère, en particulier au sein de ses unités parachutistes. Commandant par

intérim du 1er régiment étranger de parachutistes, il prend part à la tête de son régiment au putsch des Généraux en avril 1961. Hélie de Saint Marc entre dans la Résistance (réseau Jade-Amicol)

en février 1941, à l'âge de dix-neuf ans après avoir assisté à Bordeaux à l'arrivée de l'armée et des autorités françaises d'un pays alors en pleine débâcle. Arrêté le 14 juillet 1943 à la

frontière espagnole à la suite d'une dénonciation, il est déporté au camp de concentration nazi de Buchenwald.

Hélie Denoix de Saint Marc ou Hélie de Saint Marc, né le 11 février 1922 à Bordeaux et mort le 26 août 2013 à La Garde-Adhémar

(Drôme)3, est un ancien résistant et un ancien officier d'active de l'armée française, ayant servi à la Légion étrangère, en particulier au sein de ses unités parachutistes. Commandant par

intérim du 1er régiment étranger de parachutistes, il prend part à la tête de son régiment au putsch des Généraux en avril 1961. Hélie de Saint Marc entre dans la Résistance (réseau Jade-Amicol)

en février 1941, à l'âge de dix-neuf ans après avoir assisté à Bordeaux à l'arrivée de l'armée et des autorités françaises d'un pays alors en pleine débâcle. Arrêté le 14 juillet 1943 à la

frontière espagnole à la suite d'une dénonciation, il est déporté au camp de concentration nazi de Buchenwald.

Envoyé au camp satellite de Langenstein-Zwieberge où la mortalité dépasse les 90 %, il bénéficie de la protection d'un mineur letton qui le sauve d'une mort certaine. Ce dernier partage avec lui

la nourriture qu'il vole et assume l'essentiel du travail auquel ils sont soumis tous les deux. Lorsque le camp est libéré par les Américains, Hélie de Saint Marc gît inconscient dans la baraque

des mourants. Il a perdu la mémoire et oublié jusqu’à son propre nom. Il est parmi les trente survivants d'un convoi qui comportait plus de 1 000 déportés. À l'issue de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, âgé de vingt-trois ans, il effectue sa scolarité à l'École spéciale militaire de

Saint-Cyr. Hélie de Saint Marc part en Indochine française en 1948 avec la Légion étrangère au sein du 3e REI. Il vit comme les partisans vietnamiens, apprend leur langue et parle de longues

heures avec les prisonniers Viêt-minh pour comprendre leur motivation et leur manière de se battre.

Affecté au poste de Talung, à la frontière de la Chine, au milieu du peuple minoritaire Tho, il voit le poste qui lui fait face, à la frontière, pris par les communistes chinois. En Chine, les

troupes de Mao viennent de vaincre les nationalistes et vont bientôt ravitailler et dominer leurs voisins vietnamiens. La guerre est à un tournant majeur. La situation militaire est précaire,

l'armée française connaît de lourdes pertes. Après dix-huit mois, Hélie de Saint Marc et les militaires français sont évacués, comme presque tous les partisans, mais pas les villageois. « Il y a

un ordre, on ne fait pas d'omelette sans casser les œufs », lui répond-on quand il interroge sur le sort des villageois. Son groupe est obligé de donner des coups de crosse sur les doigts des

villageois et partisans voulant monter dans les camions. « Nous les avons abandonnés ». Les survivants arrivant à les rejoindre leur racontent le massacre de ceux qui avaient aidé les Français.

Il appelle ce souvenir des coups de crosse sur les doigts de leurs alliés sa blessure jaune et reste très marqué par l'abandon de ses partisans vietnamiens sur ordre du haut-commandement.

Il retourne une seconde fois en Indochine en 1951, au sein du 2e BEP (Bataillon étranger de parachutistes), peu de temps après le désastre de la RC4, en octobre 1950, qui voit l'anéantissement du

1er BEP. Il commande alors au sein de ce bataillon la 2e CIPLE (Compagnie indochinoise parachutiste de la Légion étrangère) constituée principalement de volontaires vietnamiens. Ce séjour en

Indochine est l'occasion de rencontrer le chef de bataillon Raffalli, chef de corps du 2e BEP, l'adjudant Bonnin et le général de Lattre de Tassigny chef civil et militaire de l'Indochine, qui

meurent à quelques mois d'intervalle. Recruté par le général Challe, Hélie de Saint Marc sert pendant la guerre d'Algérie, notamment aux côtés du général Massu. En avril 1961, il participe – avec

le 1er REP (Régiment étranger de parachutistes), qu'il commande par intérim – au putsch des Généraux, dirigé par Challe à Alger. L'opération échoue après quelques jours et Hélie de Saint Marc

décide de se constituer prisonnier.

Comme il l'explique devant le Haut Tribunal militaire, le 5 juin 1961, sa décision de basculer dans l'illégalité était essentiellement motivée par la volonté de ne pas abandonner les harkis,

recrutés par l'armée française pour lutter contre le FLN, et ne pas revivre ainsi sa difficile expérience indochinoise. À l'issue de son procès, Hélie de Saint-Marc est condamné à dix ans de

réclusion criminelle. Il passe cinq ans dans la prison de Tulle avant d'être gracié, le 25 décembre 1966. Après sa libération, il s'installe à Lyon avec l'aide d'André Laroche, le président de la

Fédération des déportés et commence une carrière civile dans l'industrie. Jusqu'en 1988, il fut directeur du personnel dans une entreprise de métallurgie.

En 1978, il est réhabilité dans ses droits civils et militaires. En 1988, l'un de ses petits-neveux, Laurent Beccaria, écrit sa biographie, qui est un grand succès. Il décide alors d'écrire son

autobiographie qu'il publie en 1995 sous le titre de Les champs de braises. Mémoires et qui est couronnée par le Prix Fémina catégorie « Essai » en 1996. Puis, pendant dix ans, Hélie de

Saint-Marc parcourt les États-Unis, l'Allemagne et la France pour y faire de nombreuses conférences. En 1998 et 2000, paraissent les traductions allemandes des Champs de braises (Asche und Glut)

et des Sentinelles du soir (Die Wächter des Abends) aux éditions Atlantis.

En 2001, le Livre blanc de l’armée française en Algérie s'ouvre sur une interview de Saint Marc. D'après Gilles Manceron, c'est à cause de son passé de résistant déporté et d'une allure

différente de l'archétype du « baroudeur » qu'ont beaucoup d'autres, que Saint Marc a été mis en avant dans ce livre. En 2002, il publie avec August von Kageneck — un officier allemand de sa

génération —, son quatrième livre, Notre Histoire, 1922-1945, un récit tiré de conversations avec Étienne de Montety, qui relate les souvenirs de cette époque sous la forme d'entretiens, portant

sur leurs enfances et leurs visions de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. À 89 ans, il est fait grand-croix de la Légion d'honneur, le 28 novembre 2011, par le président de la République, Nicolas

Sarkozy. Il meurt le 26 août 2013.

Bill Foxley obituary

published 15/12/2010 at 06:48 PM GMT

published 15/12/2010 at 06:48 PM GMT

Bill Foxley, who has died aged 87, was considered the most badly burned airman to survive the Second World War; his example and support became an inspiration to later generations who suffered

similar severe disabilities.

Foxley (right) in a scene from 'Battle of Britain', with Kenneth More and Susannah York

Foxley was the navigator of a Wellington bomber that crashed immediately after taking off from Castle Donington airfield on March 16 1944. He escaped unscathed but, hearing the shouts of a

trapped comrade, went back into the aircraft despite an intense fire.

He managed to drag his wireless operator free, suffering severe burns in the process. “The plane was like an inferno,” he said later. “I had to climb out of the astrodome at the top and that’s

when I got burned.” His sacrifice was not rewarded, however, as his comrade died shortly afterwards, as did two other crewmen.

Foxley was admitted to Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead, with horrific burns to his hands and face. The fire had destroyed all the skin, muscle and cartilage up to his eyebrows. He had

lost his right eye and the cornea of the remaining eye was scarred, leaving him with seriously impaired vision .

He came under the care of Sir Archibald McIndoe, the pioneering plastic surgeon, and over the next three and a half years underwent almost 30 operations to rebuild his face, including procedures

to give him a new nose and build up what was left of his hands.

He finally left hospital in December 1947, when he was discharged from the RAF as a warrant officer. Though he did his best never to let on, he was rarely free from pain for the rest of his

life.

A notable witness to his courage was Winston Churchill. During a brief convalescence in 1946 in Montreux, Foxley and a fellow burns victim, Jack Allaway, found themselves in the gardens of a

house where Churchill was painting. After watching how the two men manipulated cups of tea with their disfigured hands, Churchill walked over and offered each a cigar. Allaway reportedly then

dated Churchill’s daughter Mary.

William Foxley was born in Liverpool on August 17 1923. He was 18 when, in 1942, he joined the RAF to train as a navigator. Posted to Bomber Command, he was nearing the end of his training course

when his Wellington crashed.

After being discharged from the RAF he worked in the retail trade in Devon but wanted to return to Sussex and be near to East Grinstead. For many years he had a distinguished career in

facilities’ management at the London headquarters of the Central Electricity Generating Board, where he was the terror of contactors. Many of the workmen were unaware that he was nearly blind,

and when a redecoration job had been completed Foxley would press his face up to within a few inches of the wall and glare at it, not letting on that it was the only way he could inspect the

paint work.

Foxley had to overcome very public horror of his scarred features. Commuting daily by train from Crawley to London, the seat next to his often remained empty. Passengers who moved to take up the

seat would change their minds at the last moment, prompting Foxley to tell them: “It’s all right. I’m not going to bite you.”

In 1969 he appeared (with officer rank, for effect) in the film Battle of Britain, as a badly burned pilot who is introduced to a WAAF officer, played by Susannah York, in an celebrated scene set

in an RAF operations room.

The hospital ward at East Grinstead had been full of men who had suffered severe burns. Such was their indomitable spirit that they formed the association known as the Guinea Pig Club, in honour

of McIndoe’s pioneering and unproven surgery. Considered by its members to be more exclusive than any smart London club, the Guinea Pig provided a support network for burns victims throughout

their lives. Foxley once commented that being a “pig” meant “everything” to him.

Nor did he restrict his support to veterans of the Second World War. Foxley also gave immense encouragement to those badly burned during the Falklands conflict as well as in Iraq and Afghanistan.

With two fellow “pigs”, he set up the charity Disablement in the City, which grew into Employment Opportunities, of which the Duke of Edinburgh was president. After developing into a nationwide

organisation, Employment Opportunities merged in 2008 with the Shaw Trust.

Foxley also devoted a great deal of his time to raising funds for the Blond McIndoe Research Foundation, even getting sponsored, aged 80, to abseil down a fireman’s tower. “There’s nothing to

it,” he said afterwards.

Unable to play sport, Foxley took to long-distance running and would often run 12 to 18 miles a day, an activity he kept up until he was in his seventies. Twice he trained for the London

Marathon, but minor injuries thwarted his participation on both occasions. He rode a bicycle to the supermarket until a few months before his death and regularly paraded at the annual service of

Remembrance at the Cenotaph.

The nature of Foxley’s injuries left him unable to smile or communicate his emotions. The most animated feature of his reconstructed face was its glass eye, which glinted when it caught the

light. None the less, he never lost his positive approach to life. When asked how his experiences had affected him, he would reply: “It’s your personality that will come through, whatever. I’ve

never let it worry me too much; I’ve just got on with it.”

Bill Foxley, a remarkable and courageous man, died on December 5. He married his first wife, Catherine, who nursed him at East Grinstead Hospital, in 1947. She died in 1971. He is survived by

their two sons and by a daughter from a brief second marriage.

Agansing Rai, VC obituary

published 30/05/2000 at 12:00 AM BST

published 30/05/2000 at 12:00 AM BST

Agansing Rai, who has died in Kathmandu aged 80, was awarded the VC when serving with the 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles (Frontier Force) in Burma in 1944.

In June 1944 the 5th Gurkhas were under great pressure to stem the fanatical Japanese assault on Imphal, where success would have enabled them to break through into

India. The Gurkhas were holding the Bishenpur-Silchar track, which had already been the scene of much hard fighting.

In June 1944 the 5th Gurkhas were under great pressure to stem the fanatical Japanese assault on Imphal, where success would have enabled them to break through into

India. The Gurkhas were holding the Bishenpur-Silchar track, which had already been the scene of much hard fighting.

On 26 June, C Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Gurkhas was ordered to capture an enemy position which dominated the track and had already changed hands several times. It consisted of two

strong points, 200 yards apart and mutually self-supporting. Whereas there was dense jungle on the west of the enemy position, the hillside on the other sides was completely bare. Any assault

would have to be launched in full view of the enemy for a least 80 yards up a slippery, precipitous ridge rising to a crest.

When the Gurkha company reached the crest they were immediately pinned down by fire from machine-guns and a 37 mm gun, suffering many casualties. Agansing Rai (at that time a Naik or Corporal)

realised that delay would only lead to more casualties. So he led his section immediately at the machine-gun, firing as he charged. He killed three of the enemy machine-gun's crew of four.

Inspired by this example the Gurkha company swept forward and drove the remaining Japanese off the strong point which they then occupied.

However the Gurkhas now came under heavy fire from the other strong point, as well as from the 37 mm gun concealed in the jungle. Once again Agansing Rai led his section towards the gun. Half the

men were killed on the way, but Rai reached the gun and personally killed three of the five-man crew; his section killed the other two.

Rai then returned to his former position, took over the rest of the platoon, and in spite of heavy machine-gun fire and a shower of grenades, rushed forward with a grenade in one hand and a

Thompson sub-machine gun in the other. Having reached the position, he killed all the occupants of a bunker with his grenade and bursts of Tommy-gun fire. The remaining Japanese, thoroughly

demoralised, fled into the jungle, leaving these two vital positions in the hands of the Gurkhas.

Apart from Rai, another member of the 2/5th Royal Gurkha Rifles, Subedar Netrabahadur Thapa, also won a VC for his part in the action, which proved to be a turning point in the struggle for

Imphal.

Agansing Rai was born in the village of Amsara, in the Okhaldhunga district of Nepal on 24 April 1920. He enlisted in the 5th Gurkhas in 1941 and was posted to the second Battalion. In 1943 he

was promoted to section commander with the rank of Naik and saw action in early 1944 in the Chin Hills, where he was awarded a Military Medal.

He was presented with the VC by the Viceroy, Field Marshal Lord Wavell, in 1945. Besieged by reporters, who asked him how he felt and what he thought during the battle, he smiled disarmingly and

said: "I forget." After the war he became an Instructor at the Regimental Centre and took part in the Victory Parade in London in 1946. He then served with the 2nd/5th Gurkhas in the army of

occupation in Japan and was promoted to Subedar (company commander).

After Independence in 1947, Agansing Rai remained with the regiment in India, and in 1962-63 served in the Congo as part of the UN peacekeeping force. On retirement from the Army he was granted

the honorary rank of Lieutenant. He was presented to the Queen during her visit to Nepal in 1986.

He attended many reunions of holders of the Victoria Cross and George Cross in London, where he was much admired as a man of stature and presence. He is remembered as a wise and quiet man, but

one with a sense of humour and an ability to enjoy life.

Agansing Rai leaves three daughters and two sons.

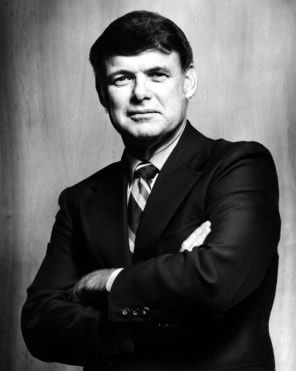

John L. ‘Jack’ Melnick, lawyer, former Virginia legislator, dies at 78

published 01/09/2013 at 15:12 PM by Adam Bernstein

published 01/09/2013 at 15:12 PM by Adam Bernstein

John L. “Jack” Melnick, a lawyer and former member of the Virginia General Assembly best-known for sponsoring legislation that created a state fund to compensate victims of major crime, died

Aug. 21 at Virginia Hospital Center in Arlington. He was 78.

The cause of death was heart ailments, son-in-law Mike Scott said.

The cause of death was heart ailments, son-in-law Mike Scott said.

Mr. Melnick, a specialist in estate, trust and probate law, began practicing law in Arlington in 1961. He spent 25 years as a commissioner in chancery of the Arlington County Circuit Court and,

at the time of death, he was a senior member of the Falls Church-based firm Melnick & Melnick, where he practiced law with his son Paul.

He served three terms in the General Assembly in the 1970s and ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic Party nomination for Virginia attorney general in 1977. The year before his bid for attorney

general, he sponsored what is now the Criminal Injuries Compensation Fund, which uses court fees to reimburse victims of felonies and serious misdemeanors for otherwise unreimbursed expenses.

The legislation, reportedly modeled on laws in England and New Zealand and more than a dozen other states, highlighted Virginia’s “moral responsibility” for victims of crime. Initially,

reimbursements were limited to $10,000 per victim; they now have a $25,000 limit.

The fund is administered by the Virginia Workers’ Compensation Commission. The fund has processed more than 25,000 claims since its inception and annually awards between $3 million and $5

million, Criminal Injuries Compensation Fund Director Mary Vail Ware said. Besides court fees and other assessments on offenders, the fund accumulates money available through grants from the

federal Office for Victims of Crime.

Ware said that, in 2008, the fund began reimbursements for all sexual assault forensic examinations in Virginia. It also has been used to provide financial support during mass-casualty incidents

in the state, including the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attack at the Pentagon and the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre.

The fund, Ware said, is used for “flights and quick counseling and funerals” until other funds become available.

John Latane Melnick was born in Alexandria and raised in Arlington, where he was a 1953 graduate of Washington-Lee High School. He was a 1958 commerce graduate of the University of Virginia and a

1961 graduate of the U-Va. law school.

Mr. Melnick, an Arlington resident, was director and a past president of the Kiwanis Club of Arlington, a past president of the Arlington Bar Association and a past member of the Virginia State

Crime Commission.

He collected antique Fords, including a Model A and a Model T.

Survivors include his wife of 51 years, Marjory Helter “Margi” Melnick of Arlington; four children, John Melnick II of Reston, Paul Melnick of Arlington and Kathy Scott and Laura Thompson, both

of Leesburg; a brother; a sister; and nine grandchildren.

Bruce C. Murray, NASA space scientist, dies at 81

published 31/08/2013 at 15:19 PM by Matt Schudel

published 31/08/2013 at 15:19 PM by Matt Schudel

Bruce C. Murray, a former director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who was an ambitious proponent of space exploration and among the first to emphasize the use of photography of other

planets, died Aug. 29 at his home in Oceanside, Calif. He was 81.

(AP) - This undated photo provided by the NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., shows former JPL Director Bruce Murray. A longtime friend said Murray died early Thursday, Aug. 29, 2013, of Alzheimer's disease. He was 81.

He had Alzheimer’s disease, the Planetary Society, an organization he helped found, announced in a statement.

Dr. Murray was director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a space exploration arm of NASA, from 1976 to 1982. He began working for the space laboratory in 1960 while serving as a geology

professor at the California Institute of Technology, which manages the JPL, based in Pasadena, Calif.

As a part of the scientific team that launched the Mariner series of missions to Mars and other planets in the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Murray was one of the first scientists to highlight the use of

photography in space science.

Mariner 4 transmitted pictures of the terrain of Mars back to Earth in 1965, the first time images of the surface of another planet had been seen. Dr. Murray used the images obtained from the

Mariner missions to develop a geological history of Mars. In the early 1970s, he was the top scientist of the Mariner 10 mission, which photographed Venus and Mercury.

Expectations were high when Dr. Murray took over the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1976. That year, two Viking missions reached Mars, dispatching automated roving vehicles to the surface, where

they collected samples of soil and rocks in an effort to determine if life existed on the Red Planet.

Dr. Murray had misgivings about the Viking projects, suggesting that they were launched before scientists had a reliable understanding of the Martian atmosphere and surface.

Later in the 1970s, two Voyager spacecraft probed the deeper recesses of the solar system, but, to Dr. Murray’s disappointment, the era of interplanetary space exploration was already at its

zenith.

He said there were two kinds of missions — purple pigeons and gray mice — that the JPL could pursue. He favored “purple pigeons,” or projects that captured the public imagination and made a big

splash in the scientific world, such as a rendezvous with a comet. “Gray mice” missions, by comparison, were less dramatic.

But Dr. Murray’s bright-hued hopes for space exploration were thwarted by continued budgetary battles with Congress and changing priorities. The space shuttle program claimed a higher profile at

NASA, as public support for the unmanned exploration of outer space began to wane.

In the early 1980s, the funding emphasis at the space laboratory began to shift from pure science to something that began to resemble an adjunct of military preparedness. Dr. Murray said he was

not necessarily opposed to the change — “Quite the opposite; I was the architect of the shift,” he said in 1982 — but he noted that other scientists were not as comfortable working on programs

with military applications.

“A number of people came to JPL over the years specifically because they did not want to work on defense projects,” Dr. Murray said. “There is a small number of people, especially young people,

who feel that defense work is immoral.”

When Dr. Murray resigned from the JPL in 1982, he was replaced by Lew Allen Jr., a retired Air Force general who had been the director of the National Security Agency.

Bruce Churchill Murray was born Nov. 30, 1931, in New York and graduated from high school in Santa Monica, Calif. He received three degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

including a PhD in geology in 1955. He was a petroleum geologist in Louisiana before serving as a scientist with the Air Force in the late 1950s.

In 1979, when he was still at the JPL, Dr. Murray and renowned scientist Carl Sagan founded the Planetary Society, which seeks to raise awareness of space science. Dr. Murray was president of the

organization for five years after Sagan’s death in 1996.

Dr. Murray was the author of several books, including “Journey Into Space: The First Thirty Years of Space Exploration” (1989). He received an exceptional scientific achievement medal from NASA

in 1971 and a distinguished public service medal in 1974. An asteroid is named in his honor.

After leaving the JPL, he returned to Caltech, where he taught until 2002. He also worked on joint U.S. space ventures with the Soviet Union, Japan and China.

His marriage to Joan O’Brien ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife of 41 years, the former Suzanne Moss; three children from his first marriage; two children from his second marriage; and

11 grandchildren.

In 2001, Dr. Murray discussed the importance of exploring Mars and other planets in an interview with United Press International.

“We want to find out, is there water? Could you build a greenhouse? Is it a potential habitat?” he said. “It’s another step in extending human mobility and our sense of what, as a species, we are

capable of.”

Inseparable couple, married for 71 years, die hours apart in northern Illinois hospice

published 30/08/2013 at 15:27 by Associated Press

published 30/08/2013 at 15:27 by Associated Press

CHICAGO — A husband and wife who eloped in 1942 and were married for more than seven decades died hours apart this week at a hospice in northern Illinois.

Family members say Robert and Nora Viands were inseparable during their marriage, which included three separate wedding ceremonies. Together, they raised five children.

“They were really never apart,” said one of their daughters, Barb Milton. “They would hold hands in the dining room.”

The two lived together in their home until moving to a Rockford retirement center earlier this year as their health deteriorated.

Robert Viands, who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease, was 92 when he died around 12:45 a.m. Wednesday. Nora Viands, 88, died at 4:45 p.m. She’d been hospitalized with pneumonia in

December.

Milton said that whenever the couple would go anywhere throughout their marriage, when their father decided it was time to leave he would tell his wife and be out the door. Robert would wait in

the car while Nora would linger, saying her goodbyes.

“We joked (after Nora died) that he was tugging on her, saying ‘Come on Nora,’ and she said ‘No, I have to say goodbye to the kids,’” Milton said.

The couple, who were originally from Ashland in central Illinois, met on a blind date. But family members say Nora wasn’t initially smitten, and vowed not to go out with him again.

Robert, who was later drafted during World War II, persisted and the two went on a second date. They eventually eloped to Missouri because at 17, Nora was too young to legally wed in Illinois. To

appease their families — she was Catholic, he was Methodist — they had two more ceremonies in their respective churches.

The couple marked their 71st anniversary in June.

Robert Viands spent 30 years working at a distributor company and retired as a rural postal carrier. He enjoyed fishing and gardening. Nora “loved a little flavor of the casinos,” according to an

obituary, and was a teacher as well as a cheerleading coach.

They also had 18 grandchildren.

Milton said she and her siblings had worried about what would happen to their surviving parent when the other one died. And though they are sad to lose them, “in our hearts we’re glad.”

“All of us children have said this is the only way they would have wanted it,” she said.

A joint funeral will be held Sunday in Rockford, about 80 miles northwest of Chicago.

Brennan Eileen

Eileen Brennan est une actrice américaine née le 3 septembre 1932 à Los Angeles, Californie (États-Unis), et morte le 28 juillet 2013 à Burbank, Californie (États-Unis).

En 1980, elle est nommée aux Oscars dans la catégorie « best supporting actress » pour son rôle dans La Bidasse (Private Benjamin). Elle joue également dans l'adaptation télévisée et est

récompensée par un Emmy Award.

Eileen Brennan est une actrice américaine née le 3 septembre 1932 à Los Angeles, Californie (États-Unis), et morte le 28 juillet 2013 à Burbank, Californie (États-Unis).

En 1980, elle est nommée aux Oscars dans la catégorie « best supporting actress » pour son rôle dans La Bidasse (Private Benjamin). Elle joue également dans l'adaptation télévisée et est

récompensée par un Emmy Award.

Filmographie

Filmographie

- 1966 : The Star Wagon (TV) : Hallie

- 1967 : Divorce American Style : Eunice Tase

- 1971 : La Dernière Séance (The Last Picture Show) : Genevieve

- 1972 : Playmates (TV) : Amy

- 1973 : L'Épouvantail (Scarecrow) : Darlene

- 1973 : The Blue Knight (TV) : Glenda

- 1973 : L'Arnaque (The Sting) : Billie

- 1974 : Come Die with Me

- 1974 : Nourish the Beast (TV) : Baba Goya

- 1974 : Daisy Miller : Mrs. Walker

- 1975 : Enfin l'amour (At Long Last Love) : Elizabeth

- 1975 : My Father's House (TV) : Mrs. Lindholm Sr.

- 1975 : Knuckle (TV)

- 1975 : La Nuit qui terrifia l'Amérique (The Night That Panicked America) (TV) : Ann Muldoon

- 1975 : La Cité des dangers (Hustle) : Paula Hollinger

- 1976 : Un cadavre au dessert (Murder by Death) : Tess Skeffington

- 1977 : The Death of Richie (TV) : Carol Werner

- 1977 : All That Glitters (série TV) : Ma Packer

- 1977 : The Last of the Cowboys : Penelope

- 1978 : Black Beauty (feuilleton TV) : Annie Gray

- 1978 : Modulation de fréquence (FM) : The Mother

- 1978 : The Cheap Detective : Betty DeBoop

- 1979 : 13 Queens Boulevard (série TV) : Felecia Winters

- 1979 : A New Kind of Family (série TV) : Kit Flanagan

- 1979 : When She Was Bad... (TV) : Mary Jensen

- 1979 : My Old Man (TV) : Marie

- 1980 : La Bidasse (Private Benjamin) : Capt. Doreen Lewis

- 1981 : When the Circus Came to Town (TV) : Jessy

- 1981 : Private Benjamin (série TV) : Capt. Doreen Lewis

- 1981 : Incident à Crestridge (Incident at Crestridge) (TV) : Sara Davis

- 1982 : Kraft Salutes Walt Disney World's 10th Anniversary (TV) : Aunt Angelique Lane

- 1982 : Working (TV) : Millworker

- 1982 : Pandemonium : Candy's Mom

- 1983 : The Funny Farm : Gail Corbin

- 1984 : Off the Rack (série TV) : Kate Halloran

- 1985 : The History of White People in America (TV)

- 1985 : The Fourth Wise Man (TV) : Judith

- 1985 : Cluedo (Clue) : Mme Pervenche

- 1986 : The History of White People in America: Volume II (TV)

- 1986 : Babes in Toyland (TV) : Mrs. Piper / Widow Hubbard

- 1987 : Le Serment du sang (Blood Vows: The Story of a Mafia Wife) (TV) : Sylvia

- 1988 : Sticky Fingers : Stella

- 1988 : The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking : Miss Bannister

- 1988 : Rented Lips : Hotel Desk Clerk

- 1988 : Going to the Chapel (TV) : Maude

- 1989 : It Had to Be You : Judith

- 1990 : Stella : Mrs. Wilkerson

- 1990 : Blossom (TV) : Agnes

- 1990 : Gravedale High (série TV) : Miss Dirge (voix)

- 1990 : Texasville : Genevieve Morgan

- 1990 : La Fièvre d'aimer (White Palace) : Judy

- 1991 : Jusqu'à ce que le crime nous sépare (Deadly Intentions... Again?) (TV) : Charlotte

- 1991 : Joey Takes a Cab

- 1992 : Taking Back My Life: The Nancy Ziegenmeyer Story (TV) : Vicky Martin

- 1992 : I Don't Buy Kisses Anymore : Frieda

- 1993 : Un meurtre si doux (Poisoned by Love: The Kern County Murders) (TV) : Martha Catlin

- 1993 : Precious Victims (TV) : Minnie Gray

- 1994 : Une femme en péril (My Name Is Kate) (TV) : Barbara Mannix

- 1994 : Nunzio's Second Cousin : Mrs. Randazzo

- 1994 : In Search of Dr. Seuss (TV) : The Who-Villian

- 1994 : Retour vers le passé (Take Me Home Again) (TV) : Sada

- 1995 : Deux mamans sur la route (Trail of Tears) (TV) : Clara

- 1995 : Un vendredi dingue (Freaky Friday) (TV) : Principal Handel

- 1995 : Reckless : Sister Margaret

- 1996 : Si les murs parlaient (If These Walls Could Talk) (TV) : Tessie (segment "1996")

- 1997 : Boys Life 2 : Mrs. Randozza (segment "Nunzio's Second Cousin")

- 1997 : Un nouveau départ (Changing Habits) : Mother Superior

- 1997 : Une fée bien allumée (Toothless) (TV) : Joe #1

- 1998 : Pants on Fire : Mom

- 1999 : The Last Great Ride : Pamela 'Mimi' Applegate

- 2000 : Moonglow

- 2001 : Dumb Luck : Minnie Hitchcock

- 2001 : Jeepers Creepers - Le chant du diable (Jeepers Creepers) : The Cat Lady

- 2002 : Comic Book Villains (vidéo) : Mrs. Cresswell

- 2003 : Treize à la douzaine (Cheaper by the Dozen) : Mrs. Drucker (DVD deleted scene)

- 2004 : The Hollow : Joan Van Etten

- 2005 : The Moguls : Mrs. Cherkiss

- 2005 : Miss FBI - Divinement armée (Miss Congeniality 2: Armed & Fabulous) : Carol Fields

Eileen Brennan dies at 80; Oscar-nominated 'Private Benjamin' star

published 30/07/2013 at 06:39 PM

published 30/07/2013 at 06:39 PM

Brennan was the epitome of the 'gruff but lovable' type who appeared on stage, TV and film. She played the growling Capt. Doreen Lewis in 'Private Benjamin' opposite Goldie Hawn.

Eileen Brennan was nominated for an Oscar for her portrayal of Capt. Doreen Lewis in 1980's "Private Benjamin." Brennan also appeared in "The Last Picture Show" and "The Sting." (Associated Press / February 20, 1980)

Eileen Brennan, a veteran actress best known for an Oscar-nominated turn in the 1980 comedy "Private Benjamin," one of her many tough-talking, soft-hearted roles, has died. She was 80.

Brennan died of bladder cancer Sunday at her home in Burbank, according to her manager, Jessica Moresco.

The actress was the epitome of the "gruff but lovable" type, often bringing comedic sparkle to workaday frustrations while playing figures worn weary by their lives but still able to laugh off

the worst.

It was in her role as the growling Capt. Doreen Lewis in "Private Benjamin," who oversaw the unlikely Army enlistee played by Goldie Hawn, that Brennan found her biggest success. The film was a

box-office hit and earned three Oscar nominations, including one for Brennan as best supporting actress. She won an Emmy for her part in the television spin-off.

Brennan was nominated seven times for Emmy Awards, including for appearances on "Taxi," 'Thirtysomething," "Newhart" and "Will & Grace."

Verla Eileen Regina Brennan was born Sept. 3, 1932, in Los Angeles to Regina Menehan, a former silent film actress, and John Gerald Brennan, a doctor. By the end of the 1950s Brennan had made her

way east, studying at Georgetown University and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. Onstage, she played the title role in the 1959 off-Broadway production of "Little Mary Sunshine" and

co-starred in the 1964 original Broadway production of "Hello, Dolly!"

She made her film debut in the 1967 comedy "Divorce American Style" starring Dick Van Dyke, Debbie Reynolds and Jason Robards. She also appeared regularly on the 1960s comedy television show

"Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In," and co-starred in the 1980 off-Broadway hit "A Coupla White Chicks Sitting Around Talking." More recently, she was in the film "Miss Congeniality 2: Armed and

Fabulous" and TV's "7th Heaven."

In Peter Bogdanovich's breakthrough 1971 film "The Last Picture Show," she played a waitress in a small Texas town diner. Brennan also appeared in Bogdanovich's 1974 adaptation of "Daisy Miller,"

his 1975 musical "At Long Last Love" and the 1990 "Picture Show" sequel "Texasville."

In 1973 she had supporting parts in "The Sting" with Robert Redford and Paul Newman and "Scarecrow" with Al Pacino and Gene Hackman.

She often excelled in roles as a wisecracking, hard-bitten sidekick, such as the madam in "The Sting" and her turns in the Neil Simon-scripted "Murder By Death" (1976) and "The Cheap Detective"

(1978). She also appeared in the 1975 crime thriller "Hustle" starring Burt Reynolds and Catherine Deneuve and 1985's murder-mystery comedy "Clue."

In a 1979 interview with The Times, as she was launching the television comedy "13 Queens Boulevard," she noted how often she was cast as comedic characters on the fringe when she said, "I've

just about exhausted the market for madams. I love to play them and I hope I have given each of the ladies a certain amount of individuality. But it's always a challenge to develop new

types."

The unexpected strength she often showed on screen came through in her off-screen life as well. In October 1982 Brennan was hit by a car in Venice and was seriously injured. Her long recovery led

to a drug addiction. After appearing in the short-lived 1984 sitcom "Off The Rack" co-starring Ed Asner, she checked into the Betty Ford Center for treatment.

She fell from the stage while appearing in a 1989 production of "Annie," breaking a leg. In 1990 she was treated for breast cancer.

Of her seemingly incredible will and survivor's strength, in a 1999 interview Brennan said, "I'm here, aren't I? What else can they do to me? The lesson is, you just take it day by day. That's

what all of us have to do.

"Some of us just have to learn it the hard way."

Her marriage to British-born poet and photographer David Lampson ended in 1973. She is survived by two sons, Sam and Patrick; two grandchildren and a sister, Kathleen Howard.

Betty Ford dies at 93; former first lady

published 09/07/2011 at 16:11 PM by Marlene Cimons

published 09/07/2011 at 16:11 PM by Marlene Cimons

The wife of President Gerald R. Ford drew on her own experience with addiction in founding famed

rehabilitation clinic.

Betty and Gerald Ford embrace in the White House in 1974. Her taboo-busting honesty — about abortion, sex, gay rights, marijuana and the Equal Rights Amendment — was a bracing antidote to the secrecy and deceptions of the Watergate era.

Former First Lady Betty Ford, who captivated the nation with her unabashed candor and forthright discussion of her

personal battles with breast cancer, prescription drug addiction and alcoholism, has died. She was 93.

Ford died Friday at the Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, according to Barbara Lewandrowski, a family representative. The cause was not given.

As wife of Gerald R. Ford, the 38th president of the United States and the only person to hold that office

without first being elected vice president or president, she spent a brief, yet remarkable time as the nation's first lady. But after he left office and even after his death in 2006 at 93, she

had considerable influence as founder of the widely emulated Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage for the treatment of

chemical dependencies.

"Throughout her long and active life, Elizabeth Anne Ford distinguished herself through her courage and compassion," President Obama said Friday in a statement. "As our nation's First Lady, she

was a powerful advocate for women's health and women's rights. After leaving the White House, Mrs. Ford helped

reduce the social stigma surrounding addiction and inspired thousands to seek much-needed treatment. While her death is a cause for sadness, we know that organizations such as the Betty Ford Center will honor her legacy by giving countless Americans a new lease on life."

Former First Lady Nancy Reagan also offered a tribute in her statement: "She has been an inspiration to so many

through her efforts to educate women about breast cancer and her wonderful work at the Betty Ford Center. She was

Jerry Ford's strength through some very difficult days in our country's history, and I admired her courage in facing and sharing her personal struggles with all of us."

Former President George H.W. Bush added, "No one confronted life's struggles with more fortitude or honesty, and as a result, we all learned from the challenges she faced."

Ford was an accidental first lady who had looked forward to her husband's retirement from political life until Richard Nixon chose him to replace Vice President Spiro Agnew, who had resigned amid

allegations of corruption. When turmoil engulfed Nixon during the Watergate scandal, she told anyone who asked that she did not want to be first lady, but the job became hers when the president

resigned on Aug. 9, 1974.

The groundbreaking role she would play as first lady may have been foreshadowed in President Ford's inaugural address.

"I am indebted to no man and only to one woman — my dear wife, Betty," he told the nation. Over the next 800 days of

his tenure, she would outshine him in the polls, and when he ran for election in 1976, one of the most popular campaign buttons read "Betty's Husband for President."

Her taboo-busting honesty — about abortion, sex, gay rights, marijuana and the Equal Rights Amendment — was a bracing antidote to the secrecy and deceptions of the Watergate era. Although her

opinions may have cost him some votes, historians and other observers would argue later that Gerald Ford

could not have ended "our long national nightmare" without Betty leading the way.

"I was terrified at first," she once said about her sudden elevation to first lady. "I had worked before. I had raised a family — and I was ready to get back to work again. Then, just at that

time, this thing happened. And I didn't have the vaguest idea what being a first lady was and what was demanded of me."

The solution? "I just decided to be myself," she said.

Ford caught the attention of a scandal-weary America with her opinions on her children's dating habits and their possible marijuana use, and on her and her husband's decision not to follow the

White House tradition of separate bedrooms.

She enthusiastically campaigned for feminist causes that she believed in — the Equal Rights Amendment, for example, and the nomination of a woman to the Supreme Court. Her vigorous support of the

women's movement inspired leading feminist Gloria Steinem to remark that she "felt better knowing that Betty Ford

was sleeping with the president."

Two months after Ford moved into the White House, a malignancy was discovered in her right breast. She underwent a radical mastectomy, followed by chemotherapy.

At that time, breast cancer was a taboo subject, so it was remarkable news that she not only disclosed the illness but openly talked about it and her treatment. "It's hard for anyone born perhaps

after 1980 or even in 1970 to understand that these things were not talked about," Dr. Patricia Ganz, director of cancer prevention and control research at UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer

Center, told The Times in 2006.

"They were very stigmatizing. A woman didn't dare mention to her friends, employer, extended family that she had breast cancer," Ganz said. Ford's belief that if it could happen to her, "it could

happen to anyone," heightened public awareness of the disease. The American Cancer Society reported a 400% increase in requests about breast cancer screenings, and tens of thousands of women

sought mammograms. Among those helped by her frank attitude was Happy Rockefeller, the wife of Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, who discovered she had breast cancer and subsequently underwent a

mastectomy.

The public outpouring led Ford to realize that when she spoke, people listened. For the rest of her White House days, she would use her position as a bully pulpit to advance the causes and issues

she believed in.

92-Year-Old on Trial for Nazi War Crime

published 02/09/2013 at 16:32 Uhr by Daniel Niemann and David Rising

published 02/09/2013 at 16:32 Uhr by Daniel Niemann and David Rising

Germany put a 92-year-old former member of the Nazi Waffen SS on trial Monday on charges that he killed a Dutch resistance fighter in 1944.

Siert Bruins , 92-year-old former member of the Nazi Waffen SS, sits in the courtroom of the court in Hagen, Germany, Monday, Sept. 2, 2013.

Dutch-born Siert Bruins, who is now German, entered the Hagen state courtroom using a walker, but appeared alert and attentive as the proceedings opened.

No pleas are made in the German system, and Bruins offered no statement. His attorney, Klaus-Peter Kniffka, said after the short 35-minute opening session that it was unlikely his client would

ever address the court personally.

"I will probably deliver a defense declaration, but it depends upon the course of the trial," he told reporters.

The trial comes amid a new phase of German Nazi-era investigations, with federal prosecutors this week expected to announce they are recommending the pursuit of possible charges against about 40

former Auschwitz guards.

The renewed probes of death camp guards come after the case of former Ohio autoworker John Demjanjuk, who died last year while appealing his 2011 conviction for accessory to murder after

allegations he served in Sobibor.

His case established that death camp guards could be convicted as accessories to murder, even if there was no specific evidence of atrocities against them.

Bruins, however, had long been on the radar of German legal authorities and already served time in the 1980s for his role in the wartime slaying of two Dutch Jews.

Bruins was also already convicted and sentenced to death in absentia in the Netherlands in 1949 in a case that involved the killing of the resistance fighter. The sentence was later commuted to

life in prison, but attempts to extradite him were unsuccessful because he had obtained German citizenship through a policy instituted by Adolf Hitler to confer citizenship on foreigners who

served the Nazi military.

Ulrich Sander, spokesman for an organization representing the victims of Nazi crimes, told the dpa news agency that the decision to bring Bruins to trial again, even at his advanced age, was a

good one.

"We must make it clear for the future that such crimes are always prosecuted, that murderers never get away," he said.

Despite his age, Bruins was found medically fit to stand trial, though Kniffka said the stress of the proceedings against him has weakened him.

Trial sessions are being limited to a maximum of three hours in deference to his age and health.

Bruins volunteered for the Waffen SS, the combat arm of the Nazis' fanatical paramilitary organization, in 1941 after the Nazis conquered and occupied his homeland. He eventually rose to the rank

of Unterscharfuehrer — roughly equivalent to sergeant.

He fought on the eastern front in Russia until 1943 when he became ill and no longer fit for combat duty.

Transferred back to the Netherlands, he served first in the Sicherheitsdienst — the Nazi internal intelligence agency — and then the Sicherheitspolizei, or Security Police, in a unit tasked to

find resistance fighters and Jews.

As part of that unit, he is accused of killing resistance fighter Aldert Klaas Dijkema in September 1944 in the town of Appingedam, near the German border in the northern Netherlands.

If convicted, he faces a possible life sentence.

Dijkema was apprehended by the Nazis on Sept. 9, 1944, on suspicion he was involved in the Dutch resistance.

According to prosecutors, Bruins and alleged accomplice August Neuhaeuser, who has since died, drove Dijkema to an isolated industrial area where they stopped and told him to "go take a

leak."

As he walked away from the car, they fired at least four shots into him, including into the back of his head, killing him instantly, according to the indictment.

Bruins and Neuhaeuser reported that Dijkema was shot while trying to escape.

Though it is not clear who fired the fatal shots, under German law if both suspects were there with the intent to kill, it does not matter who pulled the trigger, according to prosecutors.

The trial is scheduled until the end of September but it could be extended.

British Broadcaster David Frost Dead at 74

published 01/09/2013 at 16:42 PM

published 01/09/2013 at 16:42 PM

Veteran broadcaster David Frost, who won fame around the world for his interview with former President

Richard Nixon, has died, his family told the BBC. He was 74.

Frost died of a heart attack on Saturday night aboard the Queen Elizabeth cruise ship, where he was due to give a

speech, the family said. The cruise company Cunard says its vessel had left the English port of Southampton on Saturday for a 10-day cruise in the Mediterranean.

Known for incisive interviews of leading public figures, Frost spent more than 50 years as a television star.

Prime Minister David Cameron tweeted: "My heart goes out to David Frost's family. He could be — and certainly was

with me — both a friend and a fearsome interviewer.

The BBC says it received a statement from Frost's family saying it was devastated and asking "for privacy at this

difficult time."

Gordine Sacha

Sacha Gordine, prince Sacha Alexandre Gordine Gregorieff, est un producteur de cinéma , né le 27 février 1910 à Saint-Pétersbourg et mort le 8 juin 1968 à

Neuilly-sur-Seine. Sacha Gordine immigre en France en 1917 pendant la révolution russe, descendant d'une vieille famille aristocratique remontant au IXe siècle (Ivan IV de Russie le Terrible.

Personnage festif, charmeur et haut en couleur, il a à son actif une vingtaine de longs métrages et a travaillé avec des réalisateurs comme Marcel Camus, Max Ophüls, Jean Schmidt, Yves Allégret

ou Marcel Carné.

Sacha Gordine, prince Sacha Alexandre Gordine Gregorieff, est un producteur de cinéma , né le 27 février 1910 à Saint-Pétersbourg et mort le 8 juin 1968 à

Neuilly-sur-Seine. Sacha Gordine immigre en France en 1917 pendant la révolution russe, descendant d'une vieille famille aristocratique remontant au IXe siècle (Ivan IV de Russie le Terrible.

Personnage festif, charmeur et haut en couleur, il a à son actif une vingtaine de longs métrages et a travaillé avec des réalisateurs comme Marcel Camus, Max Ophüls, Jean Schmidt, Yves Allégret

ou Marcel Carné.

Il a produit certains films qui n'ont pas rencontré le public, mais aussi de grands films interprétés par Jean

Gabin, Yves Montand, Simone Signoret, Yvonne Printemps, Edwige

Feuillère, Gérard Philippe, Bernard Blier, Marcel Dalio, Pierre Fresnay, Danielle Darrieux, Catherine Rouvel... Orfeu Negro de Marcel Camus, qu'il a produit, a reçu

la Palme d'or au Festival de Cannes 1959 ainsi qu'un Oscar à Hollywood et différentes récompenses internationales.

Il monte en 1952 sa propre écurie de course automobile, l'écurie Sacha de Formule 2, avec l'intention d'aller en Formule 1, et crée la « Société des Automobiles Gordine » (SAG). Des problèmes

financiers font avorter le projet. Il a été marié à Régine Storez, première femme pilote automobile à avoir été payée pour courir. Il a eu un fils en 1954 prénommé lui aussi Sacha.

Filmographie

Filmographie

- 1944 : L'aventure est au coin de la rue

- 1945 : Jéricho

- 1946 : L'Idiot

- 1948 : Dédée d'Anvers

- 1949 : Un homme marche dans la ville

- 1949 : Barry

- 1950 : La Marie du port

- 1950 : La Ronde

- 1950 : Le Traqué de Borys Lewin, version en français

- 1950 : Gunman in the Streets (en), Traqué, de Frank Tuttle, version en anglais5

- 1951 : Les miracles n'ont lieu qu'une fois

- 1951 : Juliette ou la Clé des songes

- 1956 : La Polka des menottes

- 1958 : Premier mai

- 1959 : Orfeu Negro

- 1962 : Kriss Romani de Jean Schmidt

- 1963 : Le Tout pour le tout

Saint Marc Hélie de

Hélie Denoix de Saint Marc ou Hélie de Saint Marc, né le 11 février 1922 à Bordeaux et mort le 26 août 2013 à La Garde-Adhémar

(Drôme)3, est un ancien résistant et un ancien officier d'active de l'armée française, ayant servi à la Légion étrangère, en particulier au sein de ses unités parachutistes. Commandant par

intérim du 1er régiment étranger de parachutistes, il prend part à la tête de son régiment au putsch des Généraux en avril 1961. Hélie de Saint Marc entre dans la Résistance (réseau Jade-Amicol)

en février 1941, à l'âge de dix-neuf ans après avoir assisté à Bordeaux à l'arrivée de l'armée et des autorités françaises d'un pays alors en pleine débâcle. Arrêté le 14 juillet 1943 à la

frontière espagnole à la suite d'une dénonciation, il est déporté au camp de concentration nazi de Buchenwald.

Hélie Denoix de Saint Marc ou Hélie de Saint Marc, né le 11 février 1922 à Bordeaux et mort le 26 août 2013 à La Garde-Adhémar

(Drôme)3, est un ancien résistant et un ancien officier d'active de l'armée française, ayant servi à la Légion étrangère, en particulier au sein de ses unités parachutistes. Commandant par

intérim du 1er régiment étranger de parachutistes, il prend part à la tête de son régiment au putsch des Généraux en avril 1961. Hélie de Saint Marc entre dans la Résistance (réseau Jade-Amicol)

en février 1941, à l'âge de dix-neuf ans après avoir assisté à Bordeaux à l'arrivée de l'armée et des autorités françaises d'un pays alors en pleine débâcle. Arrêté le 14 juillet 1943 à la

frontière espagnole à la suite d'une dénonciation, il est déporté au camp de concentration nazi de Buchenwald.

Envoyé au camp satellite de Langenstein-Zwieberge où la mortalité dépasse les 90 %, il bénéficie de la protection d'un mineur letton qui le sauve d'une mort certaine. Ce dernier partage avec lui

la nourriture qu'il vole et assume l'essentiel du travail auquel ils sont soumis tous les deux. Lorsque le camp est libéré par les Américains, Hélie de Saint Marc gît inconscient dans la baraque

des mourants. Il a perdu la mémoire et oublié jusqu’à son propre nom. Il est parmi les trente survivants d'un convoi qui comportait plus de 1 000 déportés. À l'issue de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, âgé de vingt-trois ans, il effectue sa scolarité à l'École spéciale militaire de

Saint-Cyr. Hélie de Saint Marc part en Indochine française en 1948 avec la Légion étrangère au sein du 3e REI. Il vit comme les partisans vietnamiens, apprend leur langue et parle de longues

heures avec les prisonniers Viêt-minh pour comprendre leur motivation et leur manière de se battre.

Affecté au poste de Talung, à la frontière de la Chine, au milieu du peuple minoritaire Tho, il voit le poste qui lui fait face, à la frontière, pris par les communistes chinois. En Chine, les

troupes de Mao viennent de vaincre les nationalistes et vont bientôt ravitailler et dominer leurs voisins vietnamiens. La guerre est à un tournant majeur. La situation militaire est précaire,

l'armée française connaît de lourdes pertes. Après dix-huit mois, Hélie de Saint Marc et les militaires français sont évacués, comme presque tous les partisans, mais pas les villageois. « Il y a

un ordre, on ne fait pas d'omelette sans casser les œufs », lui répond-on quand il interroge sur le sort des villageois. Son groupe est obligé de donner des coups de crosse sur les doigts des

villageois et partisans voulant monter dans les camions. « Nous les avons abandonnés ». Les survivants arrivant à les rejoindre leur racontent le massacre de ceux qui avaient aidé les Français.

Il appelle ce souvenir des coups de crosse sur les doigts de leurs alliés sa blessure jaune et reste très marqué par l'abandon de ses partisans vietnamiens sur ordre du haut-commandement.

Il retourne une seconde fois en Indochine en 1951, au sein du 2e BEP (Bataillon étranger de parachutistes), peu de temps après le désastre de la RC4, en octobre 1950, qui voit l'anéantissement du

1er BEP. Il commande alors au sein de ce bataillon la 2e CIPLE (Compagnie indochinoise parachutiste de la Légion étrangère) constituée principalement de volontaires vietnamiens. Ce séjour en

Indochine est l'occasion de rencontrer le chef de bataillon Raffalli, chef de corps du 2e BEP, l'adjudant Bonnin et le général de Lattre de Tassigny chef civil et militaire de l'Indochine, qui

meurent à quelques mois d'intervalle. Recruté par le général Challe, Hélie de Saint Marc sert pendant la guerre d'Algérie, notamment aux côtés du général Massu. En avril 1961, il participe – avec

le 1er REP (Régiment étranger de parachutistes), qu'il commande par intérim – au putsch des Généraux, dirigé par Challe à Alger. L'opération échoue après quelques jours et Hélie de Saint Marc

décide de se constituer prisonnier.

Comme il l'explique devant le Haut Tribunal militaire, le 5 juin 1961, sa décision de basculer dans l'illégalité était essentiellement motivée par la volonté de ne pas abandonner les harkis,

recrutés par l'armée française pour lutter contre le FLN, et ne pas revivre ainsi sa difficile expérience indochinoise. À l'issue de son procès, Hélie de Saint-Marc est condamné à dix ans de

réclusion criminelle. Il passe cinq ans dans la prison de Tulle avant d'être gracié, le 25 décembre 1966. Après sa libération, il s'installe à Lyon avec l'aide d'André Laroche, le président de la

Fédération des déportés et commence une carrière civile dans l'industrie. Jusqu'en 1988, il fut directeur du personnel dans une entreprise de métallurgie.

En 1978, il est réhabilité dans ses droits civils et militaires. En 1988, l'un de ses petits-neveux, Laurent Beccaria, écrit sa biographie, qui est un grand succès. Il décide alors d'écrire son

autobiographie qu'il publie en 1995 sous le titre de Les champs de braises. Mémoires et qui est couronnée par le Prix Fémina catégorie « Essai » en 1996. Puis, pendant dix ans, Hélie de

Saint-Marc parcourt les États-Unis, l'Allemagne et la France pour y faire de nombreuses conférences. En 1998 et 2000, paraissent les traductions allemandes des Champs de braises (Asche und Glut)

et des Sentinelles du soir (Die Wächter des Abends) aux éditions Atlantis.

En 2001, le Livre blanc de l’armée française en Algérie s'ouvre sur une interview de Saint Marc. D'après Gilles Manceron, c'est à cause de son passé de résistant déporté et d'une allure

différente de l'archétype du « baroudeur » qu'ont beaucoup d'autres, que Saint Marc a été mis en avant dans ce livre. En 2002, il publie avec August von Kageneck — un officier allemand de sa

génération —, son quatrième livre, Notre Histoire, 1922-1945, un récit tiré de conversations avec Étienne de Montety, qui relate les souvenirs de cette époque sous la forme d'entretiens, portant

sur leurs enfances et leurs visions de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. À 89 ans, il est fait grand-croix de la Légion d'honneur, le 28 novembre 2011, par le président de la République, Nicolas

Sarkozy. Il meurt le 26 août 2013.

Generalleutnant Günther Rall obituary

published 11/10/2009 at 05:37 BST

published 11/10/2009 at 05:37 BST

Generalleutnant Günther Rall, who has died aged 91, was one of the few outstanding German fighter leaders to

survive the Second World War; by the end of the conflict he was the third-highest-scoring fighter ace

of all time with 275 aerial victories.

In postwar years he was one of the founding fathers of the modern German Air Force and rose to become its chief.

In postwar years he was one of the founding fathers of the modern German Air Force and rose to become its chief.

In the spring of 1941 Rall was a squadron commander in Jagdgeschwader (fighter wing) JG-52 flying the

Messerschmitt Bf 109 based in Romania. By this time Germany and the Soviet Union were at war and Soviet bombers were attacking the crucial oil refineries. In five days Rall and his men destroyed some 50 Soviet bombers and were next sent to the southern sector of the Eastern Front where

Rall's victories mounted rapidly against the inferior Soviet fighters and bombers.

After shooting down his 36th victim, Rall was attacked by an enemy fighter and his aircraft badly damaged. He just

managed to cross the German lines before crash landing in a rock-strewn gully. He was severely wounded and knocked unconscious but German tank crews dragged him clear. He eventually reached a

hospital in Vienna where it was found that he had broken his back in three places. Here he was treated by a woman doctor, Hertha, who later became his wife.

When Austria was annexed in 1938 Hertha had helped Jewish friends escape to London, even as Nazi discrimination and anti-Semitic policy made their lives intolerable. Indeed, while Rall was always a devoted soldier in the service of his country, when the facts of the Holocaust were presented to him he

came to look on them as "the greatest madness of this insane war".

"We knew about Dachau, the concentration camps, but not exactly what happened there," he later explained. "During the war I was hardly in Germany. The airfields were on the front, we had no idea

of what was happening behind our backs. When I heard of Auschwitz, I did not believe it. We said clearly: 'That's propaganda'."

Having been paralysed for months Rall returned to operational duty in August 1942. On September 3 he was decorated

with the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross after his 65th victory. During the following month his score increased beyond 100, bringing him the oak leaves for his Knight's Cross, the 134th

recipient of the coveted award. In November they were presented to him personally by Hitler. Afterwards, as they

sat together by the fire, Rall asked Hitler: "Führer, how long will this war take?" Hitler replied: "My dear Rall, I don't

know." That surprised him. "I thought our leaders knew everything," Rall recalled, "and suddenly I realised they

didn't know anything."

In April 1943 Rall was promoted to command III/JG-52. He was constantly in action for the next 11 months. On

August 29 he recorded his 200th victory on his 555th operational flight and on September 12 he was again summoned to Berlin when Hitler awarded him the Swords to his Knight's Cross, the 34th man to be so honoured. Rall returned to operations and in October accounted for another 40 aircraft – more than many of Germany's best pilots

achieved throughout the entire war.

As the war progressed, the obsolete Soviet fighters were steadily replaced by others with far superior performance. Nevertheless, the great majority of Rall's successes were in fighter-to-fighter combat. During his time on the Eastern Front, Rall came up against many excellent Soviet pilots and was himself shot down seven times. Finally, in April 1944, he

returned to Germany.

The son of a merchant, Günther Rall was born on March 10 1918 in Gaggenau in the Black Forest. When he was three,

his family moved to Stuttgart where he completed his education at the High School. On graduation in 1936 he joined the Army to be an infantry officer and whilst at the Dresden Kriegsschule met an

old friend whose tales of flying convinced him that he should apply to be a pilot.

During the 1930s Rall had viewed the rise of Hitler with no particular enthusiasm but, like many soldiers, approved of the way in which Hitler and the National Socialists had ended decades of humiliation for German-speaking people.

"When Hitler became chancellor," Rall remembered, "there was no unemployment, no more Rhineland occupation, no more reparations to the victors [of the

Great War]. That impressed us as young soldiers, no doubt about it."