Doris Kearns Goodwin's classic life of Lyndon Johnson, who presided over the Great Society, the

Vietnam War, and other defining moments the tumultuous 1960s, is a monument in political biography.

Doris Kearns Goodwin's classic life of Lyndon Johnson, who presided over the Great Society, the

Vietnam War, and other defining moments the tumultuous 1960s, is a monument in political biography.

From the moment the author, then a young woman from Harvard, first encountered President Johnson at a White House dance in the spring of 1967, she became fascinated by the man—his character, his

enormous energy and drive, and his manner of wielding these gifts in an endless pursuit of power.

As a member of his White House staff, she soon became his personal confidante, and in the years before his death he revealed himself to her as he did to no other.

Widely praised and enormously popular, Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream is a work of biography like few others. With uncanny insight and a richly engrossing style, the author renders LBJ in

all his vibrant, conflicted humanity.

ISBN-13 : 9780312060275

Publisher : St. Martin's Press

Publication date : 6/28/1991

Author : Doris Kearns Goodwin

Editorial Reviews

From the Publisher

"The most penetrating, fascinating political biography I have ever read . . . No other President has had a biographer who had such access to his private thoughts."—The New York Times

"Magnificent, brilliant, illuminating . . . A profound analysis of both the private and the public man."—Miami Herald

"Kearns has made Lyndon Johnson so whole, so understandable that the impact of the book is difficult to describe. It might have been called 'The Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson,' for he comes to seem

nothing so much as a figure out of Greek tragedy."—Houston Chronicle

"Johnson's every word and deed is measured in an attempt to understand one of the most powerful yet tragic of American Presidents."—Chicago Tribune

"A fine and shrewd book . . . Extraordinary . . . Poignant . . . The best [biography of LBJ] we have to date."—Boston Globe

"An extraordinary portrait of a generous, devious, complex, and profoundly manipulative man . . . [Kearns Goodwin] became the custodian not only of LBJ's political lore but of his memories,

hopes, and nightmares . . . We have it all laid out for us in this wrenchingly intimate analysis of a man who virtues, like his faults, were on a giant scale."—Cosmopolitan

"Absorbing and sympathetic, warts and all."—The Washington Post

"A grand and fascinating portrait of a most complicated, haunted, and here appealing man."—The Village Voice

"Vivid . . . No other book is likely to offer a sharper, more intimate portrait of Lyndon Johnson in his full psychic undress."—Newsweek

"Powerful, first-rate, gratifying . . . [The author] has proven herself worthy of Lyndon Johnson's trust; for by sharing his fears and dreams with us, she has helped us to understand no just one

man, but an era, and ultimately ourselves."—Newsday

Meet the Author

Doris Kearns Goodwin, the celebrated historian who is also the author of The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys and other bestsellers, has written a new foreword for this edition of Lyndon Johnson and

the American Dream. She lives in Concord, Massachusetts, with her husband and their three sons.

Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream

Livres : Textes inédits de Marilyn Monroe

published 07/10/2010 at 17:31 PM

published 07/10/2010 at 17:31 PM

Notes, poèmes, correspondances... voici un recueil de textes inédits de l'actrice Marilyn Monroe, publié

par les éditions du Seuil, qui vont ravir votre curiosité. Poupoupidou !

Véritable évènement dans l'édition, le recueil de textes inédits de l'actrice Marilyn Monroe sera

publié le 7 octobre prochain par les éditions du Seuil. La société s'est rendue détentrice des droits mondiaux et publiera l'ouvrage dans plusieurs pays, dont les Etats-Unis.

Véritable évènement dans l'édition, le recueil de textes inédits de l'actrice Marilyn Monroe sera

publié le 7 octobre prochain par les éditions du Seuil. La société s'est rendue détentrice des droits mondiaux et publiera l'ouvrage dans plusieurs pays, dont les Etats-Unis.

Des textes inédits de la star hollywoodienne, tous originaux, rassemblants des fac-similés de notes, poèmes ainsi que ses correspondances manuscrites avec le directeur de l'Actors Studio,

Lee Strasberg, ou avec sa psychanalyste, seront rassemblés dans un ouvrage de plus de 250 pages.

Des photos de l'actrice illustreront ces pages et un texte explicatif permettra de resituer les lettres dans leur contexte historique. Le premier document date de fin 1943 et le dernier de 1962,

l'année de sa mort.

Une telle entreprise a été possible grâce à Anna Strasberg, veuve de Lee Strasberg, lui-même héritier par

testament de la succession de Marilyn Monroe. Anna Strasberg a confié la publication de ces textes au

producteur Stanley Buchthal et à Bernard Comment, éditeur au Seuil.

Selon les éditeurs, Monroe évoque dans cet ouvrage les hommes de sa vie, notamment Arthur Miller. Elle livre aussi un regard critique sur son statut de pin-up hollywoodienne.

La maison d'édition française distribuera ce livre dans plusieurs pays via des maisons d'édition nationales, sélectionnées selon le prestige de leur catalogue. En Allemagne par exemple, S.

Fischer Verlag se chargera d'éditer le livre, en Espagne ce sera Seix Barral, Feltrinelli pour l'Italie et aux Etats-Unis chez Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Marilyn Monroe, Fragments, poèmes, écrits intimes et lettres - Sortie : 7 octobre 2010 - Seuil, 256 pages -

29,80 euros

Hoover’s Secret Files

published 02/08/2011 at 01:54 PM EDT

published 02/08/2011 at 01:54 PM EDT

The FBI director kept famous files on everything from Martin Luther King’s sex life to

never-before-reported secret meetings between RFK and Marilyn Monroe, as a new book reveals. An exclusive excerpt from Ronald Kessler’s 'The Secrets of the FBI.'

Complex man that he was, J. Edgar Hoover left nothing to chance. The director shrewdly recognized that building

what became known as the world’s greatest law enforcement agency would not necessarily keep him in office. So after Hoover became director, he began to maintain a special Official and Confidential file in his office. The “secret files,”

as they became widely known, would guarantee that Hoover would remain director as long as he wished.

Defenders of Hoover— a dwindling number of older former agents who still refer to him as “Mr. Hoover”—have claimed his Official and Confidential files were not used to blackmail members of Congress or presidents.

They say Hoover kept the files with sensitive information about political leaders in his suite so that young

file clerks would not peruse them and spread gossip. The files were no more secret than any other bureau files, Hoover supporters say.

While the files may well have been kept in Hoover’s office to protect them from curious clerks, it was also true

that far more sensitive files containing top-secret information on pending espionage cases were kept in the central files. If Hoover truly was concerned about information getting out, he should have been more worried about the highly classified

information in those files.

The Secrets of the FBI By Ronald Kessler, 304 pages. Crown. $26.

Moreover, the Official and Confidential files were secret in the sense that Hoover never referred to them

publicly, as he did the rest of the bureau’s files. He distinguished them from other bureau files by calling them “confidential,” denoting secrecy. But whether they were secret or not and

where they were kept was irrelevant. What was important was how Hoover used the information from those files and

from other bureau files.

“The moment [Hoover] would get something on a senator,” said William Sullivan, who became the number three

official in the bureau under Hoover, “he’d send one of the errand boys up and advise the senator that ‘we’re in

the course of an investigation, and we by chance happened to come up with this data on your daughter. But we wanted you to know this. We realize you’d want to know it.’ Well, Jesus, what does

that tell the senator? From that time on, the senator’s right in his pocket.”

Lawrence J. Heim, who was in the Crime Records Division, confirmed to me that the bureau sent agents to tell members of Congress that Hoover had picked up derogatory information on them.

“He [Hoover] would send someone over on a very confidential basis,” Heim said. As an example, if the

Metropolitan Police in Washington had picked up evidence of homosexuality, “he [Hoover] would have him say,

‘This activity is known by the Metropolitan Police Department and some of our informants, and it is in your best interests to know this.’ But nobody has ever claimed to have been blackmailed. You

can deduce what you want from that.”

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover is seen in his Washington office, date unknown

Of course, the reason no one publicly claimed to have been blackmailed is that blackmail, by definition, entails collecting embarrassing information that people do not want public. But not

everyone was intimidated.

Roy L. Elson, the administrative assistant to Senator Carl T. Hayden, will never forget an encounter he had with Cartha "Deke" DeLoach, the FBI’s liaison with Congress. For twenty years, Hayden headed the Senate Rules and Administration

Committee and later the Senate Appropriations Committee, which had jurisdiction over the FBI’s

budget. He was one of the most powerful members of Congress. As Hayden, an Arizona Democrat, suffered hearing loss and some dementia in his later years, Elson became known as the “101st senator”

because he made many of the senator’s decisions for him.

In the early 1960s, DeLoach wanted an additional appropriation for the new FBI headquarters

building, which Congress approved in April 1962.

“The senator supported the building,” Elson said. “He always gave the bureau more money than they needed. This was a request for an additional appropriation. I had reservations about it. DeLoach

was persistent.”

DeLoach “hinted” that he had “information that was unflattering and detrimental to my marital situation and that the senator might be disturbed,” said Elson, who was then married to his second

wife. “I was certainly vulnerable that way,” Elson said. “There was more than one girl [he was seeing]. . . . The implication was there was information about my sex life. There was no doubt in my

mind what he was talking about.”

8 Crazy Scenes From The Kennedys

published 13/01/2011 at 05:41 PM EST

published 13/01/2011 at 05:41 PM EST

The Daily Beast obtained an exclusive, early copy of the script of the botched History Channel miniseries The Kennedys. Jace Lacob picks eight salacious bits from the first episode.

Katie Holmes and Greg Kinnear star in The Kennedys

Ask just about anyone in Hollywood what they had thought of The Kennedys, the History Channel miniseries about the Kennedy clan, and they’ll tell you it was so far off their radars that they

didn’t give it a thought. That changed last week when the History Channel, a division of A&E Television Networks, announced that it had opted to shelve the project—from 24 co-creator Joel

Surnow, director Jon Cassar, and writer Steve Kronish—stating that the “ dramatic interpretation [was] not a fit for the History brand.”

The news was particularly shocking as The Kennedys features actors Greg Kinnear and Katie Holmes as John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy, and Tom Wilkinson as Joe Kennedy Sr. (A Canadian

broadcast of the eight-part miniseries is still set for this spring, while the project is expected to air internationally.) The show’s creators immediately began to shop the project to other

cable networks, receiving passes from FX, Starz, and, most recently, Showtime.

The Daily Beast has obtained an undated draft of the first episode of writer Kronish’s script for The Kennedys, potentially the same draft the late former Kennedy adviser Theodore C. Sorensen and

documentary filmmaker Robert Greenwald, founder of website StopKennedySmears.com, told The New York Times last winter was “political character assassination.”

The episode largely revolves around the Svengali-like grip that Joe Kennedy (Wilkinson) held over his sons, Joe Jr. (slain during WWII), war hero Jack, and lawyer Bobby (Barry Pepper), telling

his story in non-linear fashion. The action flashes between his undergraduate days at Harvard—where he was denied admission the exclusive Porcellian Club (itself recently featured in The Social

Network)—and two political campaigns being waged by John Kennedy (Kinnear), one for Congress and one the fateful presidential campaign that made him the 35th president of the United States.

But while the scene is set for JFK’s victory over Richard Nixon in 1960, Kronish seems to relish in painting the Kennedys as a group of rowdy schoolboys, equally hungry for power and sex,

particularly in the case of Wilkinson’s Joe Sr., whose quest for vengeance provides the throughline for the first episode.

What follows are eight of the most shocking moments in the script for The Kennedys’ first installment. (Kennedy obsessives, is there any truth to these dramatized events?)

One

Pages 16-17: Wilkinson’s Joe Sr. fondles his secretary in his office at the ambassador’s residence in London in 1938. As he dictates a note to the president, Joe “fondles her breasts” and

“nuzzles her neck.” When sons Joe Jr. and Jack enter his office, Joe Sr. continues his fondling as his sons look on, “amused.” The note he’s dictating? It suggests that in order to keep the peace

in Europe, certain concessions be made to Hitler. (It’s a viewpoint later parroted by son Joe Jr. even after the annexation of Czechoslovakia.) A comment made about Jack’s shabby clothes results

in him telling his father, “Girls figure I need help dressing. Once I get ‘em in the closet…”

Two

Years later, Joe Sr. and his secretary Janet pass by his wife Rose in the hallway of their Hyannisport home on Election Night 1960. After chatting with Rose, he and his secretary Janet enter his

bedroom as Rose locks her own bedroom door. [Page 57]

Three

Pages 21-23: Joe Sr. learns that Jack is romantically involved with married Danish national Inga Arvard (whom Jack refers to as “Inga Binga”), a woman that J. Edgar Hoover reports has “been

linked to counterintelligence activities in Washington on behalf of the German government.” When Jack refuses to break off relations with Arvard, Joe Sr. has Jack shipped overseas after placing a

call to the secretary of the Navy.

Four

Page 24: When beloved eldest son Joe Jr. dies during the war, Joe Sr. receives the tragic news by retreating to his bedroom alone, leaving his deeply religious wife Rose holding her rosary by

herself. Upon entering the bedroom, he spies a two-foot wooden crucifix on the wall and breaks it across his knee.

Five

Page 41: Brothers Jack and Bobby engage in banter about horniness after their father has begun to apply pressure on Jack to marry in 1951. “What do you do when you’re horny?” asks Jack. “I mean,

how can you stand the boredom?” When Bobby replies that he loves Ethel (who has just jumped into the pool during a party in McLean, at which she released live frogs), Jack says, “I love lobster,

but not every night. If I don’t have some strange ass every couple of days, I get migraines.”

Six

On Election Day 1960, Jack implies to his brother Bobby that he had sex with a redheaded aide in his campaign offices. “She volunteered to work overtime last night,” says Jack. “We discussed the

ins and outs of politics.” [Page 8]

Seven

Pages 44-46: In September 1953, while at Hyannisport, Joe Sr. tells Jackie he knows her grandfather was a Jew, changing his name from Levy to Lee so that he “could get a job on Wall Street.” In

the same conversation, Jackie tells Joe Sr. she wants a divorce from Jack. In order to keep the two together, Joe Sr. offers Jackie a $1 million trust, with the promise that if Jack doesn’t win

presidency, she can leave him and keep the money.

Eight

Page 55: Joe Sr. buys off Chicago Italian mobster Sam Giancana in an effort to help win Jack’s presidential election, telling Giancana to “get names off of tombstones for all I give a damn.” In

exchange, Joe Sr. promises Giancana protection from the Justice Department and the IRS once Jack is elected. “If you get on board—my hand to God—all you boys’ll see the best times you’ve had

since Prohibition,” he says. Giancana, of course, was said to be involved with a CIA operation in which he and other mobsters were recruited to assassinate Cuba’s Fidel Castro; Giancana was also

reputed to have shared two mistresses—Judith Exner and Phyllis McGuire—with JFK.

Editor’s Note: An early version of this story stated that Sam Giancana and John F. Kennedy were reputed to have shared one mistress, Phyllis McGuire. The text was later updated to add Judith

Exner’s name.

Plus: Check out more of the latest entertainment, fashion, and culture coverage on Sexy Beast—photos, videos, features, and Tweets.

Jace Lacob is The Daily Beast's TV Columnist. As a freelance writer, he has written for the Los Angeles Times, TV Week, and others. Jace is the founder of television criticism and analysis

website Televisionary and can be found on Twitter. He is a member of the Television Critics Association.

Like The Daily Beast on Facebook and follow us on Twitter for updates all day long.

Jace Lacob is the deputy West Coast bureau chief and television critic for The Daily Beast and Newsweek. He has written about television and culture at large, including food and cocktails, books,

film, and even the real-life sport of Quidditch. Prior to joining The Daily Beast in 2009, his work appeared in the Los Angeles Times, TV Week, AOLtv, and Film.com. He also founded Televisionary,

an award-winning television-criticism website, in 2006. He is a member of the Television Critics Association and lives in Los Angeles.

The Biggest Kennedy Myth

published 26/04/2010 at 06:36 PM EDT by Daniel Okrent

published 26/04/2010 at 06:36 PM EDT by Daniel Okrent

In an exclusive excerpt from Last Call, his history of Prohibition, Daniel Okrent writes that long-held beliefs about Joe Kennedy’s bootlegging business are bunk.

On September 26, 1933, the same day that Colorado became the 24th state to ratify the 21st Amendment repealing Prohibition, the 45-year-old Joseph P. Kennedy was aboard the S.S. Europa, bound east with a younger friend and their wives. Their primary

destination was England, where the seeds of Prohibition’s most enduring legend were about to be planted.

On September 26, 1933, the same day that Colorado became the 24th state to ratify the 21st Amendment repealing Prohibition, the 45-year-old Joseph P. Kennedy was aboard the S.S. Europa, bound east with a younger friend and their wives. Their primary

destination was England, where the seeds of Prohibition’s most enduring legend were about to be planted.

The younger man was an insurance agent named James Roosevelt. As he was also the eldest son of the new president, he was, said the Saturday Evening Post, “something like an American Prince of

Wales.” Kennedy’s fondness for his 25-year-old shipboard companion was such that he sometimes referred to himself as Roosevelt’s “foster father.” During their stay in London, one or the other of them met with Prime Minister

Ramsay MacDonald and two of his eventual successors, Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill. Together they had lunch with the managing director of the Distillers Company conglomerate. If Joe

Kennedy wanted to open political doors or commercial ones, he could have done worse than travel with the son of a president.

One writer, citing an interview with Al Capone’s 93-year-old piano tuner, actually has Kennedy coming to

Capone’s house for spaghetti dinner to discuss trading a shipment of his Irish whiskey.

By the time he returned from the U.K.—his wife had continued on to Cannes, and then to Rome with the Roosevelts for an audience with the pope—Kennedy had concluded all-but-final agreements with

Distillers to become the sole American importer of three of its most valuable brands, Dewar’s, Haig & Haig, and Gordon’s Gin. These contracts were the crucial third leg of an enterprise that

was also balanced on medicinal liquor permits—legal throughout Prohibition —that Kennedy had obtained in Washington, and the bonded warehouse space he had lined up. Shipments began arriving in

November. On December 5, Utah’s legislature became the 36th to ratify the Repeal amendment, rendering Prohibition officially dead. The next morning, before the national hangover from the previous

night’s revels had entirely subsided, Somerset Importers was in business, founded on an investment of $118,000. Kennedy’s firm took its name from the Boston men’s club that barred its doors to

Irish Catholics, and it owed its creation to Kennedy’s friendship with Franklin Roosevelt’s son. Somerset emitted the pungent air that hovered around most marriages of politics and commerce, but

it was in every respect perfectly legal.

Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. By Daniel Okrent. 480 pages. Scribner. $30

That last part—“perfectly legal”—was something that Walter Trohan, the longtime Washington bureau chief of the Chicago Tribune, failed to include in an article published some 20 years later, when

Kennedy’s son John was serving his first term as U.S. senator from Massachusetts. In that 1954 article on James Roosevelt’s impending divorce, Trohan also related the story of Joseph Kennedy’s Roosevelt-assisted entry into the liquor business. After a brief description of Kennedy’s deal

with the British, Trohan added, “At the time, Prohibition had not been repealed.” This was true, as far as it went—but it did not acknowledge that the pre-Repeal liquor Kennedy imported in

November 1933 entered the country under legal medicinal permits, and was at first stored in legally bonded warehouse space. From such acorns, nourished by a lifetime’s accumulation of rumors,

enemies, and vast sums of money, arose the widely accepted story of Joseph P. Kennedy, bootlegger.

Except there’s really no reason to believe he was one. The most familiar legacy of Prohibition might be its own mythology, a body of lore and gossip and Hollywood-induced imagery that comes close

enough to the truth to be believable, but not close enough to be… well, to be true. The Kennedy myth is an outstanding example. The facts of Kennedy’s life (that he was rich; that he was in the

liquor business; that he was deeply unpopular and widely distrusted) were rich loam for a rumor that did not begin to blossom until nearly 30 years after Repeal. Three times during the 1930s,

Kennedy was appointed to federal positions requiring Senate confirmation (chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, chairman of the U.S. Maritime Commission, Ambassador to Great

Britain). At a time when the memory of Prohibition was vivid and the passions it inflamed still smoldered, no one seemed to think Joe Kennedy had been a bootlegger—not the Republicans, not the

anti-Roosevelt Democrats, not remnant Klansmen or anti-Irish Boston Brahmins or cynical newsmen or resentful Dry leaders still seething from the humiliation of Repeal. There’s nothing in the

Senate record that suggests anyone brought up the bootlegging charge; there’s nothing about it in the press coverage that appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street

Journal, or The Boston Globe. There was nothing asserting, suggesting, or hinting at bootlegging in the Roosevelt-hating Chicago Tribune, or in the long-dry Los Angeles Times. Around the time of

his three Senate confirmations, the last of them concluding barely four years after Repeal, there was some murmuring about Kennedy’s involvement in possible stock-manipulation schemes, and a

possible conflict of interest. But about involvement in the illegal liquor trade, there was nothing at all. With Prohibition fresh in the national mind, when a hint of illegal behavior would have

been dearly prized by the president’s enemies or Kennedy’s own, there wasn’t even a whisper.

In the 1950s, another presidential appointment provoked another investigation of Kennedy’s past. This time, Dwight Eisenhower intended to name him to the President’s Board of Consultants on

Foreign Intelligence Activities, an advisory group meant to provide oversight of the Central Intelligence Agency. The office of Sherman Adams, the White House chief of staff, asked the FBI to

comb through Kennedy’s past associations and activities. The fat file that resulted touched on nearly every aspect of his life, including his business relations with James Roosevelt. But nowhere

in the file is there any indication of bootlegging in the Kennedy past, or even a suggestion of it from Kennedy’s detractors.

And so the record remained, apparently, until his son’s presidential campaign. That’s when the word “bootlegger” first attached itself to Kennedy’s name in prominent places—for instance, in a St.

Louis Post-Dispatch article dated October 15, 1960, where Edward R. Woods wrote, “In certain ultra-dry sections of the country, Joe Kennedy is now referred to as ‘a rich bootlegger’ by his

candidate-son’s detractors.” A quiet period followed, and then the suggestion started showing up again after the 1964 publication of the Warren Commission Report. Supporters of the theory that

John F. Kennedy was murdered by the Mafia suggested the assassination had something to do with the aged resentments of mobster Sam Giancana, who was, as one writer later claimed without evidence, “a former partner in Joe's bootlegging

business.”

Meyer Lansky, who’d had plenty of chances to talk about it before, suddenly claimed a pre-Repeal Kennedy

connection.

Then the mob stories burst into bloom. Meyer Lansky, who’d had plenty of chances to talk about it before, suddenly

claimed a pre-Repeal Kennedy connection. In 1973, Frank Costello told a journalist (with whom he was collaborating on a book) that he had done business with Kennedy during Prohibition; the

inconsiderate Costello proceeded to die a week and a half later. Another mobster, Joe Bonanno, repeated Costello’s assertion on 60 Minutes 10 years after that—while promoting a book of his own.

By 1991, a drama critic for The New York Times could refer to Kennedy as a bootlegger, without any elaboration, in a theater review. The same year, a potential juror in the rape trial of one of

Kennedy’s grandsons could assert without challenge, during voir dire, that the family fortune had been founded on bootlegging. By then it had become nearly impossible to ask a reasonably informed

individual to name a bootlegger without getting “Joe Kennedy” as a reply.

Some of the less reputable Joe-as-Bootlegger assertions are based on “evidence” as flimsy as one man’s recollection that he’d seen Kennedy on the docks near Gloucester, gazing out to sea, waiting

for his next shipment to come in. Never mind that during the 1920s, when he was an extremely successful stock market trader and the hands-on owner of a major motion picture studio, Kennedy might

have had more productive ways to pass his time. One writer, citing an interview with Al Capone’s 93-year-old

piano tuner, actually has Kennedy coming to Capone’s house for spaghetti dinner to discuss trading a shipment

of his Irish whiskey for a load of Capone’s Canadian. Looking backward, many find convincing evidence in the

booze Kennedy provided for his Harvard 10th Reunion—something any 33-year-old sport could have done in 1922, especially one whose father had been a legitimate tavern owner before Prohibition and

retained the right to own his remaining stock.

Others have chosen to leave shards of evidence insufficiently examined—for instance, the biographer who found a 1938 letter from Kennedy to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, in which the new

ambassador mentions his 20 years of doing business with Great Britain. The investment industry and the movie industry could have provided Kennedy with plenty of opportunity for trans-Atlantic

commerce in those years. Additionally, had the biographer realized that Hull was a life-long and active Dry, he might have been less eager to conclude that Kennedy could have been referring to

absolutely nothing else but the bootlegging business. Others have uncovered the name of a Joseph Kennedy in the transcripts of hearings conducted by the Canadian Royal Commission on Customs in

1927, but do not mention that the “Joseph Kennedy Export House” was based in Vancouver; that its eponym was identified at the time as fictitious; and that the operation in fact belonged to Henry

Reifel, a notorious British Columbia distiller who, according one prominent Canadian journalist, had simply appropriated the name of a waiter in a Vancouver bar.

Even the most reputable investigators have been unconvincing. Trying to nail down Kennedy’s putative bootlegging career, one of the finest reporters of the last 40 years tried and tried to

overcome what he called “the remarkable lack of documentation in government files.” Having failed, he chose to retail a batch of second- and thirdhand stories from people who had been

suspiciously silent for generations. A noted scholar of the Scotch Whisky industry based his case for Kennedy’s illegal activity on the memory of a Scotsman he interviewed more than three decades

after Repeal—a man who not only might have been remembering the liquor-importing Joe Kennedy of 1934, but who also, as it happened, asked his interviewer not to reveal his name, not even after

his death.

One can exonerate the old Scot of malicious intent. The Kennedy family’s rise to prominence, compounded by the increasing appearance of stray rumors in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, surely made dimly

recalled encounters from the distant past suddenly seem more meaningful (or, as the aspiring litterateurs Costello and Bonanno may have hoped, more profitable as well). But it’s harder to forgive

writers who stretch logic and research standards as if they were Silly Putty —for instance, the author of a Kennedy family biography who, unable to find substantive evidence of bootlegging,

reaches a particularly dubious conclusion: “The sheer magnitude of the recollections,” he writes, “is more important than the veracity of the individual stories.”

One cannot prove a negative. Perhaps there’s a document somewhere, or even a credible memory, that establishes a connection between Joseph P. Kennedy and the illegal liquor trade. But all we know

for certain is that Joe Kennedy brought liquor into the country legally before the end of Prohibition, and sold a great deal of it after. Along the way, the “legally” somehow fell off the page,

as it had in Walter Trohan’s 1954 article. Given nearly eight decades of journalism, history, and biography, and three trips through the Senate confirmation process, and the ongoing efforts of

legions of Kennedy haters and Kennedy doubters (and even Kennedy lovers who venerated the sons but despised the father), one would think that some scrap or sliver of evidence that he was indeed a

bootlegger would have turned up by now.

But Joe Kennedy didn’t have to be a bootlegger. After all, nearly everyone else was.

Copyright © 2101 by Last Laugh, Inc. From the forthcoming book LAST CALL by Daniel Okrent to be published by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Daniel Okrent is the author of Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. He was the first public editor of The New York Times, editor-at-large of Time Inc., and managing editor of Life

magazine. He was also a featured commentator on Ken Burns' PBS series, Baseball , and is author of four books, one of which, Great Fortune, was a finalist for the 2004 Pulitzer Prize in

history.

Like The Daily Beast on Facebook and follow us on Twitter for updates all day long.

Daniel Okrent, former public editor of the New York Times and editor-at-large at Time Inc., is the author of the just-published Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition.

Natasha: The Biography of Natalie Wood

Natalie Wood was

always a star; her mother made sure this was true. A superstitious Russian immigrant who claimed to be royalty, Maria had been told by a gypsy, long before little Natasha Zakharenko's birth, that

her second child would be famous throughout the world. When the beautiful child with the hypnotic eyes was first placed in Maria's arms, she knew the prophecy would become true and proceeded to

do everything in her power — everything — to make sure of it.

Natalie Wood was

always a star; her mother made sure this was true. A superstitious Russian immigrant who claimed to be royalty, Maria had been told by a gypsy, long before little Natasha Zakharenko's birth, that

her second child would be famous throughout the world. When the beautiful child with the hypnotic eyes was first placed in Maria's arms, she knew the prophecy would become true and proceeded to

do everything in her power — everything — to make sure of it.

Natasha is the haunting story of a vulnerable and talented actress whom many of us felt we knew. We watched her mature on the movie screen before our eyes — in Miracle on 34th Street, Rebel

Without a Cause, West Side Story, Splendor in the Grass, and on and on. She has been hailed — along with Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor — as one of the top three female movie stars in the history of film, making her a legend in her own

lifetime and beyond. But the story of what Natalie endured, of what her life was like when the doors of the

soundstages closed, has long been obscured.

Natasha is based on years of exhaustive research into Natalie's turbulent life and mysterious drowning in the

dark water that was her greatest fear. Author Suzanne Finstad, a former lawyer, conducted nearly four hundred interviews with Natalie's family, close friends, legendary costars, lovers, film crews, and virtually everyone connected with the

investigation of her strange death. Through these firsthand accounts from many who have never spoken publicly before, Finstad has reconstructed a life of emotional abuse and exploitation, of

almost unprecedented fame, great loneliness, poignancy, and loss. She sheds an unwavering light on Natalie's

complex relationships with James Dean, Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Raymond Burr, Warren Beatty, and Robert Wagner and reveals the two lost loves of Natalie's life, whom her controlling mother prevented her from marrying. Finstad tells this beauty's heartbreaking story

with sensitivity and grace, revealing a complex and conflicting mix of fragility and strength in a woman who was swept along by forces few could have resisted. Natasha is impossible to put down —

it is the definitive biography of Natalie Wood that we've long been waiting for.

ISBN-13 : 9780609809570

Publisher : Crown Publishing Group

Publication date : 04/09/2002

Author : Suzanne Finstad

Editorial Reviews

From Barnes & Noble

The fruit of nearly 400 interviews, this authoritative biography offers perhaps our first comprehensive view of a woman and movie actress whose life, until now, had remained as much a mystery as

her unexplained 1981 drowning. Finstad's zestful research illuminates every phase of Wood's abbreviated life,

from her sudden fame as a nine-year-old child star to her last night aboard The Splendour. Apparently, Ms. Wood

took her role as sex symbol seriously: The former Natasha Nikolaevna Zacharenko conducted offscreen romances with Elvis Presley, James Dean, Steve McQueen, Warren Beatty, and Robert Wagner.

Jonathan Yardley

[Finstad] helps us reach what certainly seems to be a clearer understanding of a woman who, it turns out, was even more interesting, appealing and vulnerable in private than on the screen. A

resident of Los Angeles whose previous books include a biography of Priscilla Presley, Finstad also has a keen sense of how that city's dream factory simultaneously turns women into stars and

leaves them bereft. — Washington Post Book World

Library Journal

Fans of celebrity biographies will be interested in the life story of Wood, who was born in San Francisco in 1938

to Russian immigrants, the second of three daughters. Her name was Natasha Zakharenko, later Gurdin. Positive that her dark-eyed daughter was destined for fame, Maria Gurdin got Natasha her first

screen role at age six, controlling her life and career and providing dire warnings about men and other perils. She did not dispel Natalie's terrible fear of "dark water," which Finstad repeats many times throughout the tale, leading up to the

actress's tragic drowning in 1981 at age 43. Wood's screen successes include Miracle on 34th Street, Rebel

Without a Cause, West Side Story, and The Searchers. She had male companions Raymond Burr, Dennis Hopper, and Frank

Sinatra but the great love of her life was actor Robert Wagner, whom she married, divorced, and remarried.

The mysterious circumstances of her death are reviewed in detail; Finstad conducted hundreds of interviews with friends, attorneys, the coroner, and other officials. Wood's younger sister Lana's careful reading keeps the story from sounding sensational.

Meet the Author

Suzanne Finstad, a former lawyer, is the award-winning author of five previous literary works, including the bestseller Sleeping with the Devil. She lives in Los Angeles.

Read an Excerpt

"Natalie Wood" never really existed. The actress with that name was a fictional creation of her mother, a

disturbed genius known by various first names, usually Maria. How Natalie was discovered, why she went into show

business as a child, her background, were all part of a tapestry of lies woven by Maria that began before Natalie

was even born. "God created her, but I invented her," her mother said once, after Natalie's body was discovered

floating in the dark waters off Catalina Island the Sunday after Thanksgiving of 1981, when she was just forty-three. Natalie Wood, the celebrity, was an entwined alter ego of mother and daughter so powerfully macabre her drowning had been

predicted by a gypsy, years before, to happen to Maria, not Natalie. The person inside the illusion of "Natalie Wood" was lost for years, even to herself.

Natalia Nikolaevna Zakharenko, the real name of the actress known as Natalie Wood, was a child of Russia, once

removed. Exactly where in Russia we may never know, for her mother, the source of the family history, was an unreliable witness, a feverishly imaginative woman who lived in a world of her own

invention, only occasionally punctuated by the truth. Maria's friends characterized this as colorful; others considered her devious; her youngest child eventually concluded she was a pathological

liar. There was intrigue to Maria no biographer could fully unravel. She would have three daughters -- Olga, Natalia, and Svetlana -- three sisters, as in the Chekhov play. For Maria, there was

only and ever Natalia. Her consuming obsession with Natasha, Natalia's pet name, was the one thing no one questioned about Maria.

The rest of her life was a masquerade, with Maria assuming different disguises.

Natalie Wood's mother came into the world somewhere in Siberia. It was most likely the town of Barnaul, as her

oldest child, Olga, believed and ship's records document, though she told a different daughter and a biographer that she was born in Tomsk. They are both close to Russia's border with Mongolia,

near the Altai Mountains. Maria's early years were spent in this nethermost, Russian-Asian region of the more than four and a half million square miles known as Siberia, famous for its bitterly

cold winters, romanticized for its forests primeval, and considered the ends of the earth.

Maria claimed, throughout her life, to have grown up in fantastical luxury on a palatial Siberian estate with a Chinese cook, three governesses, and a "nyanka" (nanny) per child. But her most

cherished belief, or delusion, was that she was related, through her mother, to the Romanovs, Russia's royal family. Her stories -- whether true or not, and most who heard them questioned their

veracity -- "kept you spellbound," according to a young actor who befriended Maria in the 1980s, after Natalie

drowned. "She herself was quite the actress. She spoke in a very dramatic whisper, so you had to lean in, and pay close attention. She used her hands as she would describe in great detail her

genealogy from Russia. She would whisper, 'We were descended from royalty . . .' and you would just hang on every word."

What is known of Maria's family is that her father, Stepan Zudilov, was married twice. He had four children -- two boys, Mikhael and Semen, and two girls, Apollinaria (called Lilia) and

Kallisfenia (or Kalia) -- by his first wife, Anna. Anna died in childbirth with Kalia in 1905 in Barnaul, where the Zudilovs resided. Stepan took a second bride, who would likewise bear him two

sons and two daughters in reverse order: a girl, Zoia, born in 1907, followed by Maria, then Boris and Gleb. Stepan Zudilov's youngest daughter, Maria Stepanovna Zudilova, would become the mother

of Natalie Wood.

According to Maria, her mother (also named Maria) was "close relations" to the Romanov family. It is believed her maiden name was Kulev. Whether she was an aristocrat is unknown. Kalia, Stepan's

younger daughter by his first wife and the only Zudilov child other than Maria to immigrate to the United States, would later tell her children, "Somebody in the line was a countess." But as a

Russian historian notes sardonically, "Everyone from Russia wants to be related to the Romanovs."

If Natalie Wood's grandmother had royal blood, her mother undermined her own credibility by the thousand-and-one

variations on her lineage she offered, Scheherazade-style. "One story was that her parents took her to China when she was a little girl and she became a Chinese princess through some mysterious

circumstances that were never explained," recalls a Hollywood friend. Another version that surfaced in studio biographies after Natalie became a child actress identified Maria as "being of French extraction." According to her eldest daughter, Olga,

this was a prank on Maria's part. "When they would ask her if she's French, she'd say, 'Oh, yes . . .' She knew how to speak French, because she probably had French nannies." Even this was based

solely on Maria's word, for Olga never heard her mother actually speak a word of French (nor did Maria's half-sister Kalia speak it). Maria's white lie sustained itself all the way to a 1983

television tribute to Natalie Wood, during which Orson Welles, her first costar, refers to Natalie being "not just of Russian but also of French descent." Maria, in the opinion of her daughter Lana (Americanized

from Svetlana), was "frightening" in her ability to bend reality and convince others it was true, "because she did believe everything that came out of her mouth."

Maria told Lana that she was born to gypsy parents who left her on a hillside, where the Zudilovs found her and raised her as their own. "I heard that story my entire life." Maria would laugh

about it with friends after Natalie became famous, muttering, in her heavy Slavic whisper, "They used to call me

'The Gypsy!' " She could easily create that impression as an adult, with her raven hair, magical tales and musical accent. "I could almost see her," remarked a Hollywood writer who spent hours

with Maria, "waylaying me on a street with a bunch of heather, saying, 'Buy this or you'll be cursed for life.' "

The idea that Maria was the displaced child of gypsies is "hogwash" in the pronouncement of her closest traceable living relation -- Kalia's son Constantine. No one in the family, including Lana,

took this tale seriously. It originated, Maria's daughter Olga believes, as gossip among the family servants, for Maria was born, she told Olga, at the Zudilovs' "dacha," a country cottage, in

the mountains. "And when my grandmother came back she had my mother, so the servants used to tell her, 'You were born by gypsies,' because she wasn't born right there where they could see

her."

One clue exists to help decipher Maria's past. It is a photograph of the Zudilov family, retained separately by both Maria and Kalia, taken somewhere in Russia circa March 1919, according to the

handwritten description. Maria's family, judged by their portrait, appears to be of means. They are dressed á la mode, the girls in shirtwaists and sailor dresses, posed regally, projecting a

patrician mien. Stepan Zudilov, Natalie Wood's maternal grandfather, sits on a chair to the far left of the

photograph, a stout but stately figure with a sweeping moustache, in a well-tailored three-piece woolen suit. At the center of the portrait, also seated, is his second wife, Maria, the putative

Romanov. Maria evokes a gentle womanliness. She is possessed of a round face with soft features, girlishly pretty; her dark hair, contrasted by fair skin, is styled in marcelled waves. What

distinguishes her as the grandmother of Natalie Wood are her liquid brown eyes: they hold the camera with their

tender, slightly sad gaze.

Stepan and Maria occupy the front row with their four children -- Natalie's mother, Maria, staring brazenly into

the camera's eye; thirteen-year-old Zoia; and the two boys, Boris and Gleb, six and four, seated side-by-side in identical Lord Fauntleroy suits. (Maria would later bizarrely refer to them as

"twins.") Standing behind Stepan's second family are his four grown children by his first wife, Anna; including Kalia, the corroborating witness to the family history. Anna's offspring are

swarthier, with sharper features than Stepan's children by Natalie's grandmother. Everyone has captivating

eyes.

The picture helps to solve the riddle of Maria's true age, which would become the subject of whispered speculation once she came to Hollywood. From the time she was twenty or so, she gave her

date of birth as February 8, 1912. On the back of the 1919 family photo, she is identified as "11 years, 1 month," which would mean she was born in 1908 -- the same year recorded in the ship's

log when she immigrated to America. Both Maria and Kalia, Kalia's son cheerfully admits, "lied about their age."

The photograph of Maria's family, ironically, bears a resemblance to the romantic images of Russia's Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra, in formal portraits with their children, taken in

the last days of the Romanov monarchy. Maria kept this family photo beside a framed portrait of the Romanovs in similar pose, to the day she died, prizing them as jewels. Aside from Natalie, her link to Russian aristocracy is what defined Maria to herself, true or false, for as one companion remarked,

"She believed every word of it. That's the mark of a good actress."

Musia or Marusia, as young Maria was affectionately called, was pampered from the time she was born because of her diminutive size. One of her stories was that she weighed only two pounds at

birth, nearly dying. In the family portrait, she is nestled into her mother, cradling her to her breast as Marusia peers out with the smug self-possession of the favored child. She has an elfin

quality, her dark hair pixie-short, with penetrating, bird-like eyes she compared to her father's as green, her daughter Olga describes as a changeable gray-blue, and those who considered her

malevolent called "black and beady." Her expression, even at eleven, suggests cunning. She was a mischievous girl. Her German nanny was fired for making Musia kneel; she learned to swear in

Chinese from the cook. When she did so in front of her father, it was the cook -- not Musia -- who "got a talking." The young Marusia adored jewelry (a bold bracelet leaps out from her tiny wrist

in the family photo). She collected pictures and books depicting the royal family "because I worship them," she would say later, "almost like a god."

Kalia, Marusia's older half-sister, supported her grandiose accounts of governesses and fur coats and seamstresses for their dolls, though Kalia identified the origin of the family's wealth as a

factory that produced vodka and textiles, while Maria said their father manufactured candles, ink and candy. Kalia was not heard to repeat Maria's boast that the town where they kept their dacha

was named after Natalie's grandfather. ("Because he was such a generous man. If a peasant is nice and he likes

him, he'll give him house, he gives him horse, he gives him land.") According to Maria, her parents' marriage was arranged to merge Stepan Zudilov's fortune with Maria Zuleva's name. Neither

Kalia nor Maria, once in America, had photos of the family's estate, or their dacha, to authenticate living such rarefied childhoods, though according to Kalia's son, they behaved like it.

"Didn't cook, didn't clean, had other people do that."

This idyll, if it existed, came to a tragic end around 1919. A civil war erupted in Petrograd two years before, forcing Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate. Bolshevik workers seized the Winter Palace by

October, naming Communist Vladimir Lenin as their leader. The summer of 1918, the Bolsheviks murdered Nicholas, his wife, Alexandra, and their five young children, Grand Duke Alexei and the grand

duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and presumably Anastasia.

Natalie's grandparents kept an uneasy vigil at their home in Barnaul as the Bolshevik Revolution made its way

toward Siberia. Sometime after March of 1919, the date they sat for their portrait, they were warned the Bolsheviks were coming. "They told us, 'Run!' " said Maria, "because of Mother, the whole

family would have been killed. They were killing aristocrats." They left so quickly, she recalled, there was no time to find her favorite brother, Semen.

The Zudilovs, dressed as peasants, crossed the border into Manchuria, where they stayed a few days per Maria, a year by Kalia's version. "Then the Czechs came and chased the Communists away,"

Maria recounted, "so we came back."

Marusia and her family returned to Barnaul to find Semen hanging from the archway of their front door, a rope around his neck. Ten-year-old Marusia went into violent convulsions. "I was so little

and I loved him so much -- he was such a nice half-brother. When I saw him hanging there, with the tongue and everything, I start to have convulsions, starting with the neck, then with leg and

hands, and then I just drop." The episode, a family legend, permanently affected Natalie's mother's nerves,

leaving her subject to "the fits," she called it, damaging her psyche in ways unknowable.

Marusia and her family remained in Siberia until the Bolshevik Revolution reached their door, when they fled for China, "because the Reds were killing everybody." She and Kalia would provide

essentially the same drama of the family's escape: how they packed what jewels and belongings they could onto a train their father bought from the Chinese. According to Maria, Natalie's grandfather buried "jewels and money and gold" worth "millions" in a waterproof box with a map of its location

provided to everyone in the family "except me. I was young, they didn't give me the plan." A similar story surfaced from Kalia, though never, notably, the "plan." Whether the tale of their escape

and the buried family treasure is true remains cryptic. "The problem with stories from Russians," one historian of the era observes, "is that they're all probable."

According to Natalie's mother, her parents changed everyone's names because they were afraid Communists would

find them, exacting a promise from each child never to reveal the family's true identity -- a reaction a Russian émigré friend considered extreme to the point of "demented." "Stepan Zudilov" is

identified as Kalia's father on her 1905 birth certificate, before the alleged name change, and "Maria Kuleva" is the name documented as Marusia's mother on family possessions prior to the

Revolution. These are also the names Natalie's mother would use to identify her parents on legal records once in

the U.S., leaving little room for doubt that Natalie's grandparents were born Stepan Zudilov and Maria Kuleva;

though Olga, Natalie's older sister, still expresses uncertainty those are their true names, "or if they changed

them when they ran." Olga and Natalie's mother remained haunted all her life by the fear that Communists would

come after her and "kill me like killed my brother."

Once in Manchuria, little Marusia and her family stayed at a hotel in Qiqihar, where Natalie's mother had the

first of several alleged mystical experiences. As Maria later told the story, she "recognized" a house near their hotel as one she had lived in, remembering an outdoor playhouse and the ceiling

of her bedroom, with "angels" on it. Her parents took her to the house, afraid she would have another seizure if they refused. Upstairs was a room with cherubim painted on the ceiling; in the

backyard, concealed by spiders' webs, Marusia found a decaying playhouse. Natalie's mother believed in

reincarnation ever after, despite the opposite position of the Russian Orthodox religion in which she was baptized, and to which she and her parents adhered. ("How can you explain that?" she

would ask. "There was my angels!")

Natalie's grandparents settled in nearby Harbin, China, where so many Russians had fled, neighborhoods appeared

to have been lifted out of Siberia. The family lived in such an enclave, in a "good" part of town. Stepan, Natalie's grandfather, is presumed to have managed a soap factory. Natalie's mother, Marusia, attended an all-Russian girls' school, though Marusia's eye was on "pretty young boys." She

went to church so she could "look at the boys, and look at what the girls are wearing -- is my dress better than theirs?" Marusia had thick, naturally curly, crow-black hair and was

preternaturally tiny -- just five feet -- "But she carried herself as if she were seven foot tall," an acquaintance from Maria's senior years. "She liked to talk about how she had been a great

dancer, and how she had been a great beauty." Natalie's studio press releases would later describe her mother as

a "professional ballerina" in China. "That was made up," admits daughter Olga. Teenage Marusia took one ballet class in Harbin. "For grace," she put it later, claiming her parents withdrew her,

believing dancers and performers fell into a category with "prostitutes."

Marusia and her sisters placed absolute faith in Russian superstitions and "did gypsy stuff" using Romany magic, such as "looking in the mirror on a certain night between two candles and you can

see the person you're supposed to marry." One day, the sisters had their fortunes read by a Harbin gypsy. The fortuneteller warned Marusia to "beware of dark water," for she was going to drown.

The gypsy also predicted her second child "would be a great beauty, known throughout the world." Natalie Wood's

life, and death, would be dictated by the gypsy's twin prophecies.

The fortuneteller's predictions held an immediate power over Natalie's mother. She refused to go near water,

"especially if it's dark waters."

The Mob Did It (We Think)

published 05/01/2009 at 08:06 AM EST

published 05/01/2009 at 08:06 AM EST

A new book on the JFK assassination adds credence to the theory that the mafia was at the center

of the president's murder.

The question won’t go away: Was President John F. Kennedy killed by a lone, crazed gunman

serendipitously acting out his bizarre fantasy? Or were more sinister forces at work, manipulating or taking advantage of Oswald’s act of regicide? Why hasn’t the United States government opened

all the records that illuminate this historic question?

A new book by the long-time assassination researchers Lamar Waldron and Thom Hartmann adds some new information to the legitimate accumulating literature. Legacy of Secrecy: The Long Shadow of

the JFK Assassination delves into the murder of JFK in over 800 pages of intricately documented data. It expands on their earlier Ultimate Sacrifice, which analyzed thousands of pages of released

classified documents. Their findings add pieces to one of our most perplexing puzzles, and suggest where the key missing pieces may be found.

In their new book, Waldron and Hartmann report that our government had a secret plan for a high Cuban insider to kill Fidel Castro on December 1, 1963—just days after JFK was assassinated.

The Warren Commission Report assured the world that a lone and aberrant gunman, Lee Harvey Oswald, shot the president from a hidden perch in a now infamous book depository building in Dallas.

With the stunning slaying of Oswald soon thereafter while in custody by a pseudo-patriotic, second rate Dallas hoodlum, Jack Ruby, it seemed the horrifying tragedy was ended.

But in 1966, Edward Jay Epstein’s Inquest: The Warren Commission and the Establishment of Truth seriously challenged the single bullet thesis of the Warren Commission, leading to the conclusion

that Oswald was not acting alone. Inquest did not resolve who acted with him, though speculations—then and now—abound about contemporaneous gunshots from a nearby grassy knoll.

The famous Zapruder film of the shooting (I’ve seen the full original because my former law partner was the family’s representative handling its licensing) provides graphic and commanding

corroboration of Epstein’s conclusion.

In 1974, a U. S. Senate Select Committee (the Church Committee) disclosed shocking misconduct by the CIA and the U.S. government’s aborted plans to use mafia figures (Sam Giancana and Johnny

Rosselli, both later killed by the mob) to kill Fidel Castro. In 1979, the U. S. House of Representatives Assassinations Committee unearthed troubling new wiretap evidence, concluding that 1)

Oswald did not act alone; and 2) that Jimmy Hoffa, Carlos Marcello, and Santos Trafficante, Jr. had the motive, means, and opportunity to plan and execute the assassination of JFK, setting up

Oswald as a patsy.

Case Closed (1993) by Gerald Posner, analyzed the accumulating evidence critical of the Warren Commission report and concluded, as the general American public seemed to hope, that Oswald acted

alone and that the Warren Commission’s fundamental conclusion was correct. Vincent Bugliosi’s 1,600-page Reclaiming History (2007) supported Posner’s conclusion.

My book, Perfect Villains, Imperfect Heroe: Robert F. Kennedy’s War Against Organized Crime, attempted to demonstrate that the case should not be closed and that the House Assassinations

Committee had it right, though certain critical documentation of its position was unavailable. Drawing on incriminating tapped phone conversations, new literature and investigations, and

Trafficante’s lawyer’s 1994 memoir (Frank Ragano’s Mob Lawyer), I concluded that the assassination was generated by Jimmy Hoffa. Oswald was, as he claimed, a patsy. It was a mob touch to use

someone to carry out their deadly assignments, and then to kill that person to avoid detection.

As the century ended, a congressionally mandated Assassination Records Review Commission opened some classified records, but many critical records, in the United States and in Cuba, remain secret

to this day.

In their new book, Waldron and Hartmann report that our government had a secret plan for a high Cuban insider (named in their new book) to kill Fidel Castro on December 1, 1963—just days after

JFK was assassinated. It would be followed by an invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles aided by the U. S. military. It was managed off the books by Robert Kennedy and a select group of government

officials and the military. The mafia learned of it, and after its furtive, aborted plans to kill Kennedy weeks earlier in Chicago and Tampa failed, they arranged for him to be killed in Texas,

knowing that our government could not disclose these facts without admitting its own provocative plans and endangering worldwide retaliation. It was, assassination expert Jefferson Morley quipped

in The Washington Post, “a deus ex mafia”.

Waldron’s and Hartmann’s new revelations in Legacy of Secrecy add newly released government recordings of Carlos Marcello in prison, claiming to have arranged the assassination. Trafficante’s and

Rosselli’s attorneys both have reported that their clients claimed responsibility for the assassination. Along with Marcello’s confession, and credible information that has eked out from

mentioned sources, the evidence points to a conspiracy case that could go to a jury—were the parties alive.

Interviews with Kennedy aide Dave Powers, who rode close behind the president in the fatal motorcade, disclosed that he saw and heard evidence of shots from the grassy knoll, and that he was

subject to “intense pressure to get him to change his testimony ‘for the good of the country’.” Presidential assistant Kenneth O’Donnell agreed. Later sound, visual, and medical

studies—persuasive but controverted—confirm their and other on-the-scene observers’ opinions, and the Edward Epstein thesis.

The Waldron-Hartmann books suggest why the grieving Attorney General and the powerful government authorities at the time failed to aggressively pursue all leads based on the government’s prior

dealing with the mob. Robert Kennedy could not pursue them because his own misconduct would have come to light, and knowledge of it would have had serious foreign policy implications. Those few

investigative officials who knew of the critical facts had every reason to hide them.

The Warren Commission relied in its investigation on the obvious investigating authorities at the time, the FBI and CIA. Both agencies, especially the CIA, had intramural interests for

dissembling and hiding the true facts. Lyndon Johnson later questioned that conclusion, his aides reported. RFK told aides he would pursue the true facts when he became president.

A German documentary film, Rendezvous With Death, included an interview with a former Cuban secret service agent who said the Cuban Secret Service was responsible for the JFK assassination, using

Oswald as its hired gun. After Fidel Castro is out of power, Cuban records—if they exist—could corroborate that story. Castro told an AP reporter days before the Kennedy assassination that he

knew plans were afoot to assassinate him and that if the US pursued those plans—plans we know did exist, and which Waldron-Hartmann books document—our president’s life would be in danger. Days

later that scenario played out. An American agent met a Cuban Castro assassin in Paris, and our president was shot.

The Waldron-Hartmann books do not resolve the case. Many more government records remain to be released. It is now nearly a half century later, and there is no good reason not to release the

voluminous secret records which may clarify the important, continuing mystery behind this epic American tragedy. Hopefully, the new Obama administration will open all these records as part of its

proclaimed policy of openness and transparency. Hiding information always raises suspicions. Open information policies are more likely to lead to truthful conclusions. It is time the world knew

every bit of available information about the assassination of JFK.

Ronald Goldfarb is a veteran Washington, D.C., attorney, author and literary agent who worked in the Department of Justice as a special assistant to Robert F. Kennedy in the organized crime and

racketeering section, and as a speechwriter for Kennedy’s Senate campaign in New York. He has written 11 books and 300 articles in addition to numerous op-eds and reviews (see

www.RonaldGoldfarb.com).

Like The Daily Beast on Facebook and follow us on Twitter for updates all day long.

Patrick Albert T.

Albert T. Patrick immediately after his release in 1913

Albert T. Patrick was a lawyer who was convicted and sentenced to death at Sing Sing for the murder of his client William Marsh Rice. Patrick was born in Texas during the 19th century. He was charged with conspiring to murder Rice on 24 September 1900, convicted on 26 March 1902 and sentenced to be electrocuted. His appeals of the conviction delayed the execution of the sentence. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by Governor of New York Frank W. Higgins in 1906. Doubts about the evidence caused the Governor John Alden Dix to pardon him in 1912. In 1930 he was disbarred and the disbarment was upheld by the New York State Supreme Court. It was said that the conduct of the case during the 12 years between being charged and being pardoned cost Patrick and his friends $162,000.

Pollack Jack

James H. "Jack" Pollack (21 October 1899 – 14 March 1977) was an American Democrat politician known for criminal pursuits and interference in court system. Pollack was born in Baltimore, Maryland

and lived in a home near the intersection of Wilson and Exeter Streets during his childhood. However, the death of his mother at age 13 and the death of his father at age 15 forced him to quit

school and live on the streets. Pollack found his place in the streets of Baltimore through competitive boxing. Pollack travelled the country competing for $1,500 dollar purses in lightweight

title fights. At 175 pounds Pollack was a stout fighter who won acclaim for fighting men as much as 40 pounds heavier.

Pollack also made a name for himself during prohibition as a whiskey-runner. From a residence on West Fayette Street, Pollack organized whiskey smuggling under the claimed profession of

"chauffeur". From 1921 to 1926, Pollack was arrested 13 times on charges that ranged from assault to murder. Pollack was charged with the murder of Hugo Caplan in 1921 during the hijacking of a

contraband whiskey truck. Two years later, Pollack was acquitted of the charges and the files disappeared from the State's Attorney's office in 1948. Pollack gained some local fame within from

his prohibition activities.

Pollack gained notoriety and political success during the 1930s with the creation of the Trenton Democratic Club. He used his ties with Baltimore politician William Curran to form a political

base amongst area Democrats. Pollack saw major involvement in the Baltimore court system as a tool for political success. His relationships with jurists made him well known for payoffs, bribery,

and corruption. In 1954, he beat a charge on obstruction of justice in which he pressured defendants in a series of corruption trials. Pollack was well respected despite some blatant criminal

activity while in politics. He was appointed to the Maryland State Athletic Commission in 1933 by Governor Albert Ritchie. Pollack remained active in politics until his death from cancer on 14

March 1977 at University Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

Luciano's Luck

In the darkest days of World War II, an American Mafioso is the Allies’ only hope to tip the scales of victory. The classic

Jack Higgins thriller : As the Allies struggle to gain a foothold in Italy in 1943, American gangster Charles

“Lucky” Luciano is pulled from his prison cell in New York by the U.S. military and handed a top-secret mission. Lucky must go to Sicily to persuade a distrustful Mafia to revolt against the island’s fascist occupiers.

In the darkest days of World War II, an American Mafioso is the Allies’ only hope to tip the scales of victory. The classic

Jack Higgins thriller : As the Allies struggle to gain a foothold in Italy in 1943, American gangster Charles

“Lucky” Luciano is pulled from his prison cell in New York by the U.S. military and handed a top-secret mission. Lucky must go to Sicily to persuade a distrustful Mafia to revolt against the island’s fascist occupiers.

If successful, Lucky’s mission will pave the way for a full-scale invasion of Italy and aid the advancing Allied

forces in breaking Hitler’s grip on the nation once and for all. But if he fails, the toll in human blood will be higher than anyone can imagine.

ISBN-13 : 9781453200599

Publisher : Open Road Integrated Media LLC

Publication date : 06/28/2010

Author : Jack Higgins

Editorial Reviews

Library Journal

Dove Audio goes to the head of the pack with this exciting, unabridged rendition of Higgins's (Sheba, Audio Reviews, LJ 2/15/95) story of an Allied plan to release Lucky Luciano from prison. Luciano is slated to join a team that includes the granddaughter of Luciano's Mafia

counterpart in Sicily and a crack Special Services operative. Their objective: to persuade the Don to rally the people of Sicily to aid the Allies in their effort to run the Axis forces off the

island, paving the way for the Allied invasion of Italy. The action builds to a riveting climax and concomitant bloody conclusion. British actor and former Avenger Patrick Macnee is required to

juggle Sicilian, German, American, and Ukrainian accents and does so superbly. Best of all, this unabridged recording is reasonably priced. Recommended for most public libraries.Mark Pumphrey,

Polk Cty. P.L., Columbus, N.C.

Meet the Author

Since The Eagle Has Landed—one of the biggest-selling thrillers of all time—every novel Jack Higgins has written has become an international bestseller. He has had simultaneous number-one

bestsellers in hardcover and paperback, and many of his books have been made into successful movies, including The Eagle Has Landed, To Catch a King, On Dangerous Ground, Eye of the Storm, and

Thunder Point. He has degrees in sociology, social psychology, and economics from the University of London, and a doctorate in media from Leeds Metropolitan University. A fellow of the Royal

Society of Arts, and an expert scuba diver and marksman, Higgins lives in Jersey on the Channel Islands.

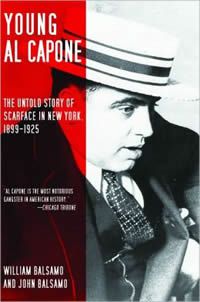

Capone: The Life And World Of Al Capone

The public called him Scarface; the FBI called him Public Enemy Number One; his associates called him Snorky. But Capone is the name most remember. And John Kobler’s Capone is the definitive biography of this most brutal and flamboyant of the underground kings—an intimate and dramatic

book that presents a complete view of Al Capone and his gaudy era.

The public called him Scarface; the FBI called him Public Enemy Number One; his associates called him Snorky. But Capone is the name most remember. And John Kobler’s Capone is the definitive biography of this most brutal and flamboyant of the underground kings—an intimate and dramatic

book that presents a complete view of Al Capone and his gaudy era.

Here is Capone’s story: his violent childhood in Brooklyn, his lieutenancy to Johnny Torrio, his rise in the ranks of the underworld, the notorious St. Valentine Massacre, his eventual control of the

entire city of Chicago, and his decline during his imprisonment in Alcatraz. Capone was the ultimate gangster,

and Capone is the ultimate in gangster biographies—a classic in the literature of crime.

ISBN-13 : 9780306812859

Publisher : Da Capo Press

Publication date : 10/7/2003

Author : John Kobler

Mr. Capone: The Real and Complete Story of Al Capone

All I ever did was to sell beer and whiskey to our best people. All I ever did was to supply a demand that was pretty popular. Why, the very guys that make my trade good are the ones

that yell the loudest about me. Some of the leading judges use the stuff.

All I ever did was to sell beer and whiskey to our best people. All I ever did was to supply a demand that was pretty popular. Why, the very guys that make my trade good are the ones

that yell the loudest about me. Some of the leading judges use the stuff.

When I sell liquor, it's called bootlegging. When my patrons serve it on silver trays on Lake Shore Drive, it's called hospitality. — Al Capone

In 1930 Al Capone was the most famous American alive. Now, the bestselling author of Geneen, the acclaimed

biography of ITT founder Harold Geneen, reveals the real Capone and how he ran his operation. Schoenberg's

scrupulous research shows that Capone was a man as calculating and brutal as his legend. Photos.

ISBN-13 : 9780688128388

Publisher : HarperCollins Publishers

Publication date : 09/28/1993

Author : Robert J. Schoenberg

Meet the Author

Robert J. Shoenberg, a former advertising executive, is the author or two other books, including Geneen, a much-praised biography of ITT founder Harold Green.

St. Valentine's Day Massacre

St. Valentine's Day Massacre: The Untold Story of the Gangland Bloodbath That Brought Down Al Capone. The machine-gun murders

of seven men on the morning of February 14, 1929, by killers dressed as cops became the gangland crime of the century." Or so the story went.

St. Valentine's Day Massacre: The Untold Story of the Gangland Bloodbath That Brought Down Al Capone. The machine-gun murders

of seven men on the morning of February 14, 1929, by killers dressed as cops became the gangland crime of the century." Or so the story went.

Since then it has been featured in countless histories, biographies, movies, and television specials. 'The St. Valentine's Day Massacre, ' however, is the first book-length treatment of the

subject, and it challenges the commonly held assumption that Al Capone ordered the slayings to gain supremacy in the Chicago underworld."

ISBN-13 : 9781581825497

Publisher : Turner Publishing Company

Publication date : 08/28/2006

Author : William J. Helmer, Arthur J. Bilek

Comments

The Saint Valentine's Day massacre is the first time the shooting of seven members of the north side gang was but into a full biography. The book was based on a careful review of reliable

evidence, a critical reading of reading of news accounts by the authors William J. Helmer and Arthur J. Bilek, and a widow of one of the gunmen, and a lookout¿s long detailed confession.

Throughout the story the authors are able to set up an image of 1920's Chicago, during the time of prohibition, and illegal bootlegging of alcohol. Through this method of imagery, the authors are

also able to use the background of Chicago¿s beer wars, the victims, and the gunmen, to allow the reader to feel as if the crimes are currently occurring. On the morning of February 14, 1929 in

the SMC Cartage Company A four-man team led by Fred Burke would then enter the building, two disguised as police officers, Capone¿s men disguised as cops lined the mechanic and six members of the

north side gang against the wall and repeatedly shot them with Thompson machine guns killing all seven.

The hit was a setup for Bugs Moran, but Moran never showed up. To show by-standers that everything was under control, the pair in street clothes came out with their hands up, led by the two

uniformed cops. Alphonse Gabriel Capone was cheifly behind the murders of the seven men. Capone was an American gangster who led a crime syndicate dedicated to the smuggling and bootlegging of

liquor and other illegal activities during the Prohibition Era of the 1920s and 1930s. And by wiping out head members of the north side gang Capone would be able to climb on top of the industry

with no competitors. The time frame was the roaring twenties in Chicago during the Prohibition in the United Through the use of detailed imagery Helmer and Bilek are able to set up a written

visual of the scenarios around the crime. The era of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the years 1920 to 1933, during which alcohol sale, manufacture and transportation

were constitutionally banned throughout the United States. Prohibition can also encompass the antecedent religious and political temperance movements calling for sumptuary laws to end or encumber

alcohol use.

Prior to the St. Valentines Dat massacre there were brutal gang wars between Capone¿s gang and Moran¿s gang. The crime itself was provoked by Moran and previous attempts on Capone¿s life. By

thoroughly discussing the Chicago beer wars and events stirring up the bad blood between these two gangs the authors are able to allow the reader to understand the timing and significance of the

St. Valentines day massacre. Overall the St. Valentines day Massacre is a very interesting book to read, and gives the reader a better knowledge of the crime. Through the authors factual writing

the biography of the crime serves as a far more informative account of the crime and the 1920's Chicago gangs, then any other previous collections of these events. Allowing the reader to become

aware of the beginning and end of the Chicago beer wars, and Capone¿s empire.

Jensen Jan Krogh

Jan "Face" Krogh Jensen (August 23, 1958 – June 16, 1996) was a Danish mobster and member of the Bandidos Motorcycle Club. He emigrated to Helsingborg, Sweden and co-founded White Trash MC,