published 18/06/2013 at 12:11 PM by Megan McDonough

published 18/06/2013 at 12:11 PM by Megan McDonough

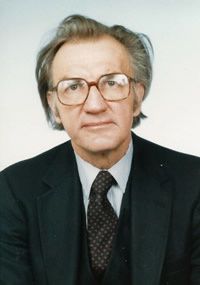

William Z. Slany, a top State Department historian who helped oversee a study in the 1990s that exposed Nazi looting of Jewish property and that led to $8 billion in belated compensation for

Holocaust victims and their families, died May 13 at his home in Reston. He was 84.

The cause was heart ailments, said his former wife, Beverly Zweiben.

The cause was heart ailments, said his former wife, Beverly Zweiben.

Dr. Slany was the State Department’s chief historian from 1982 until his retirement in 2000. He drew the most attention for a massive, two-part study that burrowed into the history of Nazi

Germany to expose the methodical theft of Jewish property.

The stolen assets encompassed jewelry and other valuables belonging to victims of the regime’s persecution. The looting was so extreme as to include gold teeth taken from concentration camp

victims.

In addition, many European Jews had turned to Swiss banks for safekeeping of their savings during Hitler’s rule. Many of those account holders did not survive the Holocaust. Decades later,

questions remained about the status of their assets.

A new wave of interest in the dormant, unclaimed accounts came in 1995, after then-Sen. Alfonse D’Amato (R-N.Y.) launched Senate banking committee hearings after being urged on by the World

Jewish Congress.

The next year, President Bill Clinton tapped Stuart E. Eizenstat, an undersecretary of state who had served as a special envoy for property claims in Central and Eastern Europe, to investigate.

Eizenstat asked Dr. Slany to help.

As the chief historian and principal author of the reports, Dr. Slany oversaw the declassification of nearly 1 million pages of documentation and the indexing of more than 15 million pages by the

National Archives and Records Administration.

With contributions from 11 federal agencies, the report was one of the largest interagency historical efforts undertaken by the executive branch.

In an interview, Eizenstat praised Dr. Slany’s “credibility, integrity [and] sharp historian’s eye.”

“They should have been called the Slany Reports because he was the one that envisioned the work plan, stitched together the information, and drafted the report,” he said. “This was his product

from start to finish.”

According to the investigation, many of the stolen assets were stored in ostensibly neutral nations, including Sweden, Portugal, Spain, Turkey and Argentina. The report’s sharpest criticism was

of Switzerland, which was estimated to have possessed as much as $400 million in looted gold.

“The massive and systematic plundering of gold and other assets from conquered nations and Nazi victims was no rogue operation,” Eizenstat said in the 1997 preliminary report. “It was essential

to the financing of the German war machine.”

That report also emphasized the shortcomings of the United States, particularly government officials’ reluctance after the war to aggressively seek compensation for Holocaust victims.

Jim Hoagland, a Washington Post foreign affairs columnist, called the preliminary report “a Matterhorn of integrity and truth-telling.” The initiative encouraged more than a dozen nations to set

up their own investigative commissions. It also has been credited with setting the groundwork for later settlements, including a landmark $1.25 billion settlement by Swiss banks with Holocaust

survivors and their families.

↧

William Z. Slany, historian who exposed Nazi theft of Jewish property, dies at 84

↧